Call for Papers Submission Guidelines Back Issues Current Issue

New Women: Who's Who Gallery Home The Whine Cellar

Bibliography

|

|

The New Woman in Context

By Molly O’Donnell

Introduction

Depictions of the New Woman with cigarettes, rational dress, bicycle, and bobbed hair made her instantly recognizable to her contemporaries, and her visual and textual representation in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries are contextually revealing.

Loose conceptions of race combined with nationalist pride to trigger fears of people perceived to be outside the borders of normative behavior, appearance, or class. Stereotypes such as the New Woman, the Decadent, the Irishman, the Jew, or the indigenous colonial native were amply evident in the popular press (and either minimized or managed with levity or context). The suggested proximity of such stereotypes such as the New Woman and say, a native of the Congo—despite their obvious differences—revealed cultural anxieties and attempts to neutralize them. Evidence from the American popular press at the time suggests these same sentiments were expressed (sometimes more forcefully) in the States. See the following small sample from a much larger cultural archive:

Figure 1

The Puck (America’s Punch) page in Figure 1 illustrates several associations between the figure of the New Woman and African Americans. At the top left of the page (excerpted below in Figure 2), we are introduced to the topic of the “unwomanly” woman (a subject familiar relatable to the New Woman).

Figure 2

The implication of Figure 2 is that the father’s assumptions (that Griselda is a woman, hence without sexual desire) have been dashed by the mother’s answer to her daughter’s curiosity.

Figure 3

Further down the same page as illustrated in Figure 3, we get a similarly themed joke (marital troubles). This one recounts a New Woman introducing the issue of a sexless marriage, “Lovers Once, But Married Now.” The long-held assumption of the trouble of the New Woman resulted from a shortage of men (and subsequent “odd women”) or dissatisfaction at the state of marriage trivialized the serious issues surrounding the early feminist movement concerning the rights of married women.

Figure 4

Perhaps the most prominent aspect on the page is the cartoon depicting the black couple in Figure 4. Here we get not only the grimace-worthy dialogue one can expect for the time, but the marital strife caused by the courting Watson’s infidelities.

Contextually, what can perhaps be drawn from these layered depictions of domestic tranquility interrupted is that sexual continuity within the confines of marriage is not guaranteed; more often than not, it is actually undesirable from the woman’s point of view. In the only courting couple depicted in the cartoon, we see that even prior to marriage, the faith has been broken. By overtly situating these issues in the realm of the outsiders (the New Woman and the black couple), the effrontery of dangerous extramarital sexuality is neutralized, and their transgressions are subtly associated. If this was not the case, would it not be just as humorous to have a white woman accuse her suitor of smelling of another woman? Or to have an ordinary housewife say that the spark had gone out of her relationship because she was now married?

Figure 5

A convert from Judaism, it is perhaps ironic that Benjamin Disraeli offers us the most complete portrait of the Englishman’s understanding of the Irish in the nineteenth century: “[The Irish] hate our free and fertile isle. They hate our order, our civilization, our enterprising industry, our sustained courage, our decorous liberty, our pure religion. This wild, reckless, indolent, uncertain, and superstitious race have no sympathy with English character. Their fair ideal of human felicity is an alternation of clannish broils and coarse idolatry. Their history describes an unbroken circle of bigotry and blood” (1836; cited in Curtis’ Anglo-Saxons 51). What becomes obvious is a systematic bigotry on the part not of the Irish but of the conservative English.

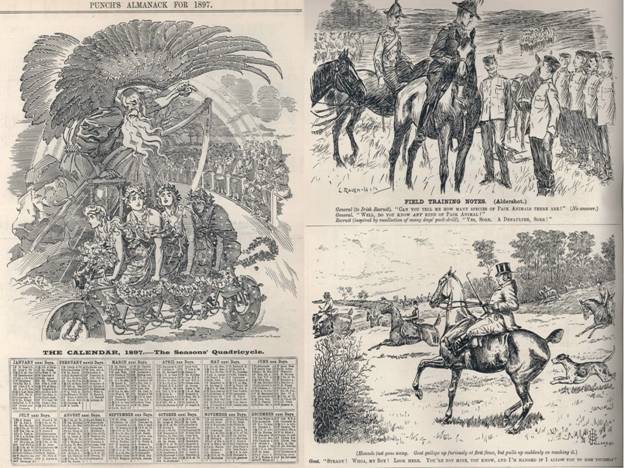

In the first image, illustrated in Figure 5, we see the New Woman’s bike exaggerated into a quadra-tandem, with each season looking progressively more weathered from her pedaling as she nears the winter of her life. Set against this image on the facing page is a cartoon depicting the cowardice and stupidity of Paddy: “Gen. (to Irish recruit): Can you tell me any species of pack animal? Recruit: Yes, sorr, a defaulter, sorr.”

Figure 6

Above the cartoon illustrated in Figure 6, we note a reference to the artificial fashion of New Womanism: “The clothes make the New Woman,” and nothing more (center-left). It is worth donning the props of the New Woman if fashionable, much as the Jewish father only sees the worth of his sons’ acrobatics if they result in a monetary gain. At the base of both accusations and their nearness to each other is an element of disingenuousness, and a lack of substance.

Figure 7

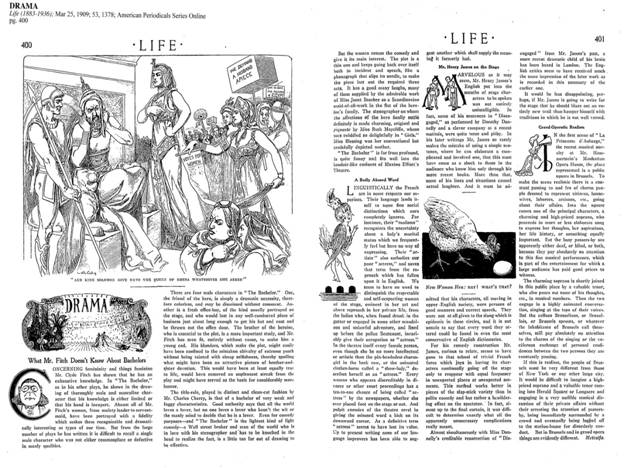

The 1909 copy of Life laid out in Figure 7 introduces the New Woman’s unfitness for motherhood with a cartoon that equates women’s suffrage with women’s dissatisfaction in not finding a husband (presumably because they’re ugly). This is followed by a review of a play called The Bachelor, in which the title character has to be goaded or deceived into marriage.

All of this placement seems to serve the next page well because we have an illustration of a woman dressed in a bird costume on the same level as a New Woman hen who can’t recognize her own egg (“What’s this?”). Her unfitness for motherhood is preempted by the contextual evidence that she wanted a husband, couldn’t get one, and is now forced to see that she is wasting her own potential as a mother (it is an egg not a chick that the hen sees).

Figure 8

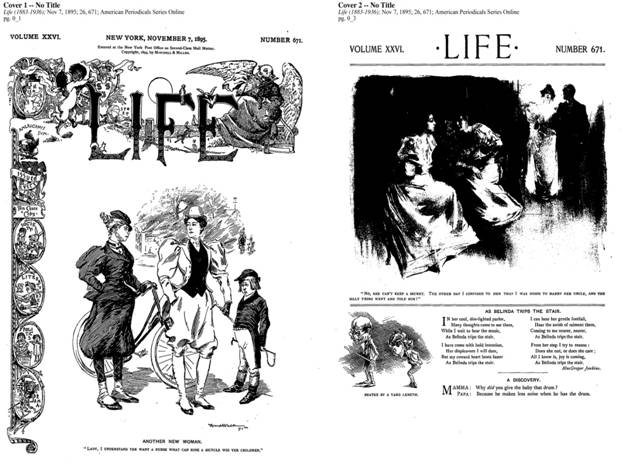

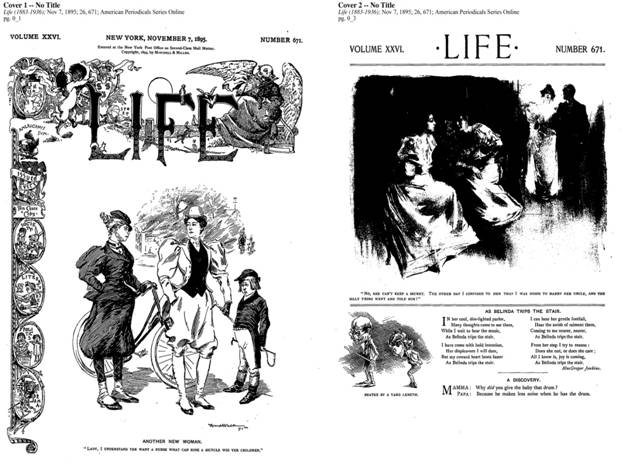

In Figure 8’s 1895 cover of Life, the New Woman in her bicycle suit is less unattractive, but equally ridiculous. Cover 2 (right) illustrates an aspiring/scheming wife, underscored by a cartoon of a brow-beaten husband. Is this a sequence of events? Does the ridiculous New Woman with her cycling nanny preview a frightening home life where the domineering and scheming wife is in charge?

Figure 9

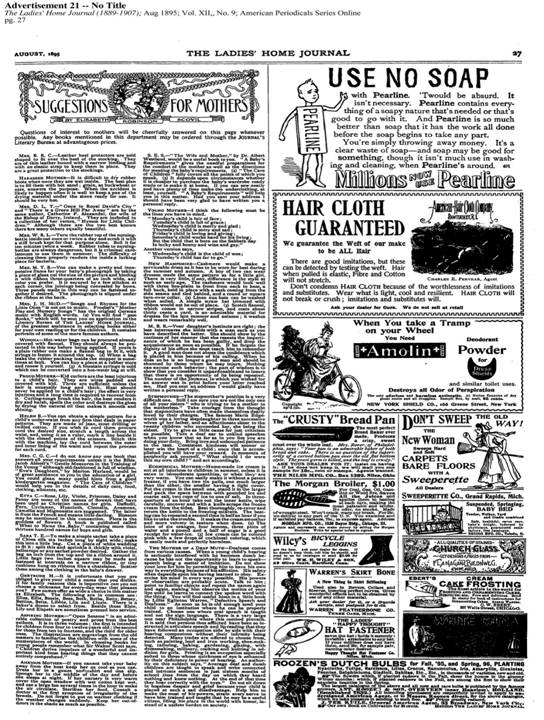

Women’s magazines, on the other hand, seemed to take a softer approach to the New Woman, perhaps subverting her threat to serve the purposes of advertisers, or in an attempt to avoid alienating New Womanish readers. They offer a sort of reassurance that though times might be changing, women are still the same at heart. As can be seen in the Ladies’ Home Journal page of Figure 9, the New Woman out on her bike is set next to advice for mothers; she is also depicted cleaning her house. The message is clear: the New Woman is still woman, mother, housekeeper. Granted, the Ladies’ Home Journal might be more geared to a homemaker in general as subject matter. One might assume that this would caution the editors against taking up the subject of the New Woman at all, but this doesn’t seem to be the case. Instead, they directly engage the New Woman as just another type of reader, which also somewhat neutralizes her effect.

Figure 10

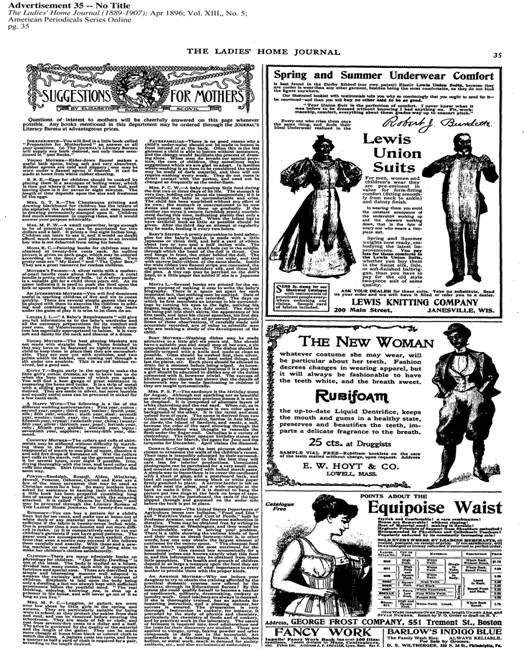

In Figure 10 the New Woman is still corseted, though her corset is now meant for cycling. Ladies’ Home Journal seems to suggest that New Womanism is a fashion fad. Here the New Woman is depicted in all her glory as someone very concerned with white teeth. Just below this is another corset ad. To the left items we find terms such as “the happy wife” and “housemother.”

Conclusion

Exploring images of the New Woman in context suggests a few both old and new concepts. First, denigrating New Women through association with other loathed subcultures (e.g., the black, Irish, Asian, Jewish, spinster) was a popular method of attack. Second, comparing New Womanism with a fashion fad trivialized the seriousness of New Woman phenomenon. Third, the press’s rhetoric suggested that the reality of the New Woman was still essentially female, but subject to greater risk because of aging and a physically weaker condition. Fourth, similar to the last rhetorical position, the New Woman was presented as an unfit mother because of her incompetence and childishness. And last, the New Woman was seen as a bad wife, or held responsible for failed romantic relationships.

In this cursory examination of the ladies’ magazines, it appears that the image of the New Woman was also a handy marketing tool that actually reflected traditional feminine values, much as the fashion fad argument operated to neutralize the power of the subculture. Images of the New Woman, then, though often prevalent and powerful, also had significant contextual implications meant to contain, subvert, and perhaps deny her identity and potential as a threat to middle-class Western ideologies of the day, even when these images were presented as seemingly superficial entertainment.

|