Latchkey Home Book Reviews Essays Conference News Featured New Women

New Women: Who's Who GalleryThe Whine Cellar

Teaching Resources Bibliography

Contact us

|

|

“Real or Imaginary Facts”: Spectral Sensations and Embodied Vision in Vernon Lee

By Anne Summers.

In her 1880 essay “Comparative Aesthetics,” Vernon Lee casts art in a ghostly light, arguing “The artistic form has no physical existence: it is a phantom, but in this phantom is the real life of the art” (303). This metaphorical linkage of artistic forms and phantoms speaks to a larger preoccupation visible across Lee’s prolific career, as her essays and novels continually explore the seemingly disparate subjects of supernatural experience and aesthetic perception. Lee’s characterization of art not as a static entity but as a “shifting, changing mental conception” (303) emphasizes the correspondence between each individual observer and the sights she sees; like an apparition, which may be visible to some while invisible to others, artistic form fluctuates based on the subjective perceptions of each viewer.

While the recent resurgence of critical interest in Lee has certainly addressed both her engagement with aesthetics and the supernatural, particularly in her well-known short story collection Hauntings (1890), few critics have discussed the occult in her first novel, Miss Brown (1884) or fully investigated what occult experience in Miss Brown means for the novel’s larger conceptualization of sensory perception. 1 In her descriptions of both occult ritual and aesthetic engagement, Lee draws these distinct subjects together through a shared focus on the deeply embodied experience of looking; she meticulously tracks the quivers, shudders, and sighs that human viewers release while looking at objects, spirits, or bodies, highlighting the powerful role of physiological response in perceptual exchange. Lee also connects both occult practices and aesthetic enjoyment through a shared experience of erotic sensation, revealing an eroticism born of visual engagement that extends into encounters with both material objects and apparent supernatural manifestations. Through comparison of Lee’s illustration of visual perception in Miss Brown and her later writings on psychological aesthetics, this essay highlights previously unexplored connections between Lee’s aesthetic principles and her first novel, investigating Miss Brown’s relationship to a larger network of fin-de-siècle psychological theories which explored the complex relationship between human physiological response and aesthetic form. When situated in the context of Lee’s shared interest in aesthetics and the occult, visual experience emerges as an essential component of Lee’s larger construction of a fictional vision based on a profusion of interchanging subject positions, rather than an environment organized around rigid divides between self and other, animate and inanimate, and real and imaginary entities, in which discrete identities often collapse in favor of moments of merger and connection between apparently distinct bodies, minds, and material objects.

Supernatural Skeptics in Miss Brown

Miss Brown, a satirical reimagining of the life of a model in aesthetic society, traces the social trajectory of the title character, Anne Brown, as she moves from housemaid to the upper ranks of Pre-Raphaelite London after attracting the interest of painter and poet, Walter Hamlin. Over the course of the novel, Anne becomes London’s most famous model and artistic muse and eventually agrees to marry Hamlin, despite her growing distaste for the aestheticist community and for Walter Hamlin himself (II: 17). Hamlin, who serves as a fictional representative of a decaying aestheticism that Lee mercilessly condemns throughout the novel, often deploys objectifying visual practices; when sketching Anne Brown, for instance, he tries to copy her likeness “as he would copy the shape of a handsome vase, without wondering what there may be inside” (I: 28). 2 Hamlin routinely ignores Anne’s individuality and collapses her identity into a series of female “types,” taken from a long line of female bodies recorded in plaster and paint. 3 As Kathy Psomiades notes, Walter’s obsessive interest in Anne is based on her resemblance to various fragments pulled from distinct visual and cultural locations; as a result, he views her as a collage of diverse representational pieces instead of a cohesive and unique human subject (Beauty’s Body 166). In this way, Lee’s early representation of Anne Brown as aesthetic muse reveals the powerful connection between vision and an oppressive, controlling heterosexual desire. When Anne is painted by Hamlin and his friends and eventually showcased around fashionable London in an effort to further Hamlin’s prestige, Lee hints that this brand of visuality “is based on an erotic theft, a feeding off the bodies of women that vampire-like wastes the real body … for the sake of the textual body” (“Still Burning” 23). 4

Hamlin and his aesthete cronies are affiliated with the occult through their interest in séances, spiritualism and mesmerism, opening up space for an investigation of the text’s treatment of the occult in relation to Lee’s larger conceptualization of visual perception. Lee refers to both mesmerism and spiritualism in Miss Brown. These practices were often aligned with various other occult trends during the Victorian period. As Elaine Gomel has explained, “Occultism swallows up motley discourses whose only shared feature is ideological disenfranchisement. Spiritualism, for example, allied itself with phrenology, mesmerism, homeopathy, and vegetarianism, though in none of them did spirits play any discernable part” (196). Like many famous Victorians, some of the central Pre-Raphaelite figures, including D. G. Rossetti, were known to participate in séances (Fredeman 50). In Miss Brown, Edmund Lewis, a fellow painter and close friend of Hamlin’s, runs séances for the London aesthetes and attempts to mesmerize Anne. Vision was a crucial element of mesmerism, since prolonged, unbroken eye contact was supposedly the key to enacting a trance (Winter 31). As the vehicle through which Lewis attempts to both exert his mesmeric influence and record the appearances of figures and forms in his art, Lewis’s visual capabilities are central to his identity not only as an aesthete but a mesmerist as well. In fact, when describing Lewis, Lee’s narrator continually calls attention to his eyes, which often “glitter … like that of a snake” (II: 143).

When spirits themselves appear to surface in Miss Brown, their reality is immediately

questioned. When attending a “grand spiritualistic séance” halfway through the

novel, Anne Brown does not discover many believable supernatural manifestations. Anne’s friend Marjory attends the séance with the express purpose of “unmask[ing] some sort of trickery” and manages to cast doubt on the validity of the supposed supernatural activity after discovering that a wreath that appears, suspended in the air and held by “spirit hands,” is made not of real laurels but of a mass of cheap “stamped paper [which] left a green stain in the hand” (III: 6). While some of the guests join Marjory in scoffing at the proceedings, others are alert, excited, and engaged. Lee takes pains to show the circulation of coexistent skepticism and belief in the séance room, explaining “The séance, to which Edmund Lewis had brought a famous professional medium, was very much like any other séance: a darkened room, a company of people partly excited, partly bored; expectation, disappointment, faith, incredulity; moving of tables and rapping, faint music, half visible hands” (III: 5). Lee’s treatment of ghostly apparitions and mesmeric trances is ostensibly more about sensory experience than it is about the supernatural; her depiction of the occult lingers on discussion of potential for trickery and illusion, asking characters and readers to practice discerning truth in an environment where their eyes and ears may deceive them. Investigation of these spirits and séances is, therefore, a powerfully perceptual experience, calling for “a constant negotiation between what can be seen and what is in the shadows” (Gordon 17), as participants must remain alert, searching for signs of truth or deception encoded in brief flashes of “half visible hands.”

On the surface, the occult practices represented in Miss Brown may appear little more than the silly, self-gratifying pastimes of men like Hamlin and Lewis who seek to satisfy their own egos, either by overpowering female mediums through mental penetration (Lewis) or by proving themselves important enough to attract the notice of spirits (Hamlin). As a result, it is easy for readers to take Anne Brown’s skepticism at face value and dismiss these séances simply as hoaxes or as additional evidence to highlight the restrictive, highly gendered visual practices of Anne’s social sphere. But if we examine Miss Brown’s engagement with these occult practices in the context of Lee’s larger interest in the supernatural, we discover that the absence of believable ghostly manifestations in Miss Brown is not necessarily problematic for Lee. In fact, it might be part of her point. Lee’s essay “Faustus and Helena: Notes on the Supernatural in Art,” first published in Cornhill in 1880, reveals Lee’s interest in spirits not as embodiments of the dead but as psychological phenomena. When Lee refers to a ghost, she means not that “vulgar apparition which is seen or heard in told or written tales; [but] the ghost which slowly rises up in our mind; the haunter, not of corridors and staircases, but of our fancies.” Her description of the supernatural, which she defines as “nothing but ever-renewed impressions, ever-shifting fancies,” is closely aligned with a perceptual experience throughout the essay. As she explains, “a ghost is the sound of our steps through a ruined cloister … it is the scent of mouldering plaster and mouldering bones from beneath the broken pavement; a ghost is the bright moonlight against which the cypresses stand out like black hearse-plumes.” Through her use of sensory metaphor, Lee fuses mental “fancies” and bodily feeling, describing the ghost as a “vague feeling … pleasing and terrible” which “invades our whole consciousness,” striking the individual and sparking “confusedly embodied” reactions (222). Despite the fact that ghosts might not actually appear, an individual’s “confusedly embodied” responses are thus exciting pieces of psychological data for Lee.

As Avery Gordon argues, we can claim that ghosts are “real” and worthy objects of critical study because “they produce material effects” in the environments in which they purportedly emerge (17). In Miss Brown, the supposed signs of ghostly presence—the “moving of tables and rapping, faint music, half visible hands” of the séance—may very well be fraudulent but they still spark reactions in the bodies and minds of the séance sitters. For Lee, mental responses and bodily sensations, from that simultaneous circulation of diverse mental reactions (“expectation, disappointment, faith, incredulity”) to the gasps, sighs, eye-rolls, laughs, and shudders that the participants offer in response to these apparent occult manifestations, expose the precarious division between our own “fancies” and the supposedly objective material world that we perceive around us. Lee argues that because philosophy has “maintain[ed] the immaterial and independent quality of mind,” we have been led to believe that the mind is “quite separate from this real material universe and hence unworthy of practical consideration.” But Lee explicitly contests this separation, claiming instead that “The things in our mind, due to the mind’s constitution and its relation with the universe, are, after all, realities; and realities to count with, as much as the tables and chairs and hats and coats” (Renaissance Fancies 239). Lee’s occult vision is thus one method by which she entangles the real and imaginary, refusing to consistently privilege the so-called “real material universe” over “the things in our mind.”

Sights and Sighs in the Gallery

While vision is a common thread that we can use to draw occult ritual and aesthetic engagement together, to better understand how aesthetics and the occult intersect in Lee, we must also investigate Lee’s complex aesthetic principles, which she crafted and revised obsessively throughout her career. The connection between her later theories and her depiction of aesthetic and occult viewing in Miss Brown has not received much critical attention, perhaps because Lee’s psychological aesthetics theories were not fully formed until the turn of the century. But Benjamin Morgan has noted that as far back as 1880, four years before the publication of Miss Brown, Lee was already formulating aesthetic ideas that bear resemblance to her later theories (35). In particular, he notes that in “Comparative Aesthetics,” published in The Contemporary Review’s August issue of that year, Lee describes art as “not shapeless, lawless fluid: [but] an organic physico-mental entity” (306), a characterization that proves strikingly similar to her discussions in her 1912 book, Beauty and Ugliness and Other Studies in Psychological Aesthetics (306). Similarly, I argue that early traces of Lee’s interest in the correspondence between subjective experience and material reality emerge in Miss Brown, exposing fruitful links between Lee’s later theorizations of aesthetic perception and her early fictional work.

In the 1890s, along with her personal and professional partner, Clementina (Kit) Anstruther-Thomson, Lee developed a series of experiments and writings aimed at achieving a better grasp of the complex relationship between physicality and aesthetic form. Before these experiments, Lee had already established herself as a devotee of Walter Pater in her early work on aesthetics, which displayed her interest in assessing the value of art based on the individual’s unique responses and impressions. While Lee would expand her purview to include depictions of the viewer’s physiological reaction in a way that Pater did not, we can nonetheless see Pater’s interest in the subjective impressions of the viewer as central to Lee’s aesthetic theories. Pater’s famous questions in The Renaissance - “What is this song or picture ... to me? What effect does it really produce on me? Does it give me pleasure?. . . How is my nature modified by its presence, and under its influence?” - (Preface viii) are thus essential starting points for understanding Lee’s aesthetic principles . 5

Lee and Anstruther-Thomson’s research began with a visit to an art gallery in March 1894, when to Lee’s amazement, Anstruther-Thomson reported that she could feel her breathing changing depending on which painting she looked at (Maltz 214). Their subsequent writings and lectures, including the essay “Beauty and Ugliness,” published in The Contemporary Review in 1897, attempted to make sense of this phenomenon in hopes of discovering definitive proof of the intimate relations between bodies and art and the value of artistic perception to human health (214). Lee continued to revise and expand their findings; she kept detailed notes of her gallery visits from 1901-1904, published the full-length book Beauty and Ugliness in 1912, the short primer The Beautiful in 1913, and a collection of Kit’s notes and lectures in Art and Man in 1924 (Davis 176). Overall, Lee’s aesthetic theories, which changed frequently throughout her life and were rife with contradictions and retractions, stressed the close-knit connection between the viewer and the art object, seeking justification for Lee’s conviction that “whatever abstract instinct for beauty we may possess, it is only through physical sensations that this instinct is reached” (Belcaro 210).

As critics like Carolyn Burdett and Benjamin Morgan have noted, Lee’s interest in the body’s lively participation in aesthetic experience was deeply embedded within a larger web of contemporary scientific inquiry. In Beauty and Ugliness, Lee quotes from an extensive list of European and Anglo-American scientists, demonstrating the vast extent of her research into the fields of psychology and physiology (Burdett 5). Morgan positions Lee’s work within a theoretical tradition stretching back to Edmund Burke which “treated aesthetics as a science of perception” and argued “that aesthetic pleasure was best understood as the body’s response to form, color, and sound” (27-28). In addition, Grant Allen’s 1877 Physiological Aesthetics, which Lee read, was particularly instrumental in inspiring the rise of combined studies of body and beauty in the latter part of the nineteenth century (Burdett 7).

Lee also makes extensive use of the German term Einfühlung, implementing the concept to better theorize the relationship between the viewer and the larger enticing world of beautiful things. Einfühlung first surfaced in Robert Vischer’s On the Optical Sense of Form (1873), where the term was used to describe the process by which “humans instinctively project themselves into the objects they see” (Morgan 34). Einfühlung soon emerged as a central concept amongst psychological aesthetics scholars and was utilized by German philosophers and psychologists like Theodore Lipps and Karl Groos. In 1909, Einfühlung was first translated into English as “empathy” (Burdett 1). For a period during the early twentieth century, then, “empathy” was used in psychological aesthetics circles to denote “an unconscious physiological reaction to an object” before the word transitioned to the more human-centric meaning popularly used today (Morgan 32). Although Lee and Anstruther-Thomson had not employed the term Einfühlung in their 1897 text, 6 by the time of Lee’s publication of the extended version of Beauty and Ugliness in 1912, she had adopted the concept, using it to adequately summarize what she saw as a “project[ion] [of] ourselves in external phenomena” through perception, an experience in which the human viewer “feel[s] oneself into” a painting or a picturesque natural setting, effectively “transporting…our own human nature” into that material object or scene (Beauty and Ugliness 47).

In the 1897 “Beauty and Ugliness,” Lee and Anstruther-Thomson provide readers with detailed descriptions of the typical methods of their gallery experiments which depend heavily on physical perception. When gazing at a chair, for instance, Anstruther-Thomson tracks her own bodily reactions down to their most minute fluctuation:

While seeing this chair, there happen movements of the two eyes, of the head, and of the thorax, and balancing movements in the back ... The chair is a bilateral object, so the two eyes are equally active. They meet the two legs of the chair at the ground and run up both sides simultaneously. There is a feeling as if the width of the chair were pulling the two eyes wide apart … Recognition of the height of the chair, begun with pressure of both feet on the ground, is accompanied by an upward stretch of the body. (548-49)

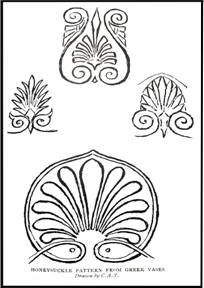

According to this description, visual perception of a chair initiates a mysterious process by which the body mirrors the structure of the inanimate object, stretching upward in “recognition of the height of the chair” while both eyes engage equally in response to its “bilateral” nature. Lee and Anstruther-Thomson record similar reactions to a variety of aesthetic objects, from Doric columns, visual patterns etched into vases (Figure 1), and church architecture, to a group of Renaissance paintings, finding in perception of each object additional proof of this connection between the human self and the material world, through which some boundary between the viewer and the object itself is breached. When examining the interior of a church, for example, Anstruther-Thompson feels “the church as a larger circumference of ourselves” (564). She even claims to experience this feeling of fusion when looking at a blank wall, arguing “The space in front of us seems to come forward as if to swallow us up. We feel as if our profile were flattened, and as if in some extraordinary way we had lost identity” (553). Through these references to intermingling, expansion, and imitation, Lee and Anstruther-Thomson utterly reject understandings of the self as a bounded unit neatly separated from the world that surrounds it. In Lee’s estimation, perception can apparently divest us of the illusion that we are neatly differentiated from our environment and the other inanimate and animate beings that inhabit it, revealing what Christa Zorn calls Lee’s rejection of “the dichotomy of mind and matter, or, likewise, of subject and object” as “a purely idealist manner of thinking” (65). Using another ghostly allusion, Lee even confesses that her sensations of connection with the nonhuman world of statues and paintings is so intense that it causes the human world to fall away: “Oddly the vague, shifting, gravityless movements (if such they can be called) of the crowd do not worry me: they are like ghosts compared with the statues and me” (Beauty and Ugliness 301).

Figure 1. Clementina Anstruther-Thomson, “Honeysuckle Pattern from Greek Vases,” Beauty and Ugliness (1912)

Lee also charts how different subjective variables converge to influence an individual’s visual experience in the gallery. In the excerpts from her gallery diaries, Lee records looking at paintings both with and without her glasses, with the curtains closed and open, while stationary and in motion, and from different distances in order to track how these changes affect her bodily sensation and assessment of the artwork. Lee’s discussion also extends to the role of emotions in altering perception, as she describes how the viewer’s visual experience might change if she is sad or preoccupied. Lee summarizes her attention to these particularities, arguing that our reaction to art “varies from day to day, and is connected with variations in our mental and also our bodily condition… there exist in experience no such abstractions as aesthetic attention or aesthetic enjoyment, but merely very various states of our whole being which express themselves… in various degrees and qualities of responsiveness” (Beauty and Ugliness 243). Lee and Anstruther-Thomson had come to a similar conclusion in their earlier 1897 version. When tracing the apparent fluctuation of an “objective pattern of form,” the women note that “the pattern of our senses of adjustment tallies most absolutely in every detail with the pattern of the particular object we are looking at; for the simple reason that the subjective patterns of our perceptive feelings and the objective pattern of the form perceived are one and the same phenomenon differently thought of” (227). As Morgan highlights, these descriptions do not characterize the body and mind as distinct entities; instead, the two are framed as “inseparable,” allowing the body to emerge as “an important source of knowledge” throughout their writing (41). Just like the “fancies and fears” of the mind that give rise to the supposed manifestation of ghostly figures in the material world, the subjective and objective in aesthetic viewing are not only linked, but are exposed as one in the same, a singular “phenomenon differently thought of.”

In the 1912 Beauty and Ugliness, Lee often describes her experiences of Einfühlung as rapturous and sensual, particularly when she calls attention to the mixture of herself with female bodies and forms. To explain the relationship between experiences of “pleasure and displeasure” and “perception of visible shape,” Lee cites Santayana, acknowledging his claim that an “increase of aesthetic sensitiveness [is] connected with sexual development” (140). In an excerpt from her gallery diaries in which she examines a work by Giorgione, Lee digresses to discuss her attraction to a female painted form:

Certain blues and lilacs catch me at once with a sense of slight bodily rapture, unlocalised but akin to that of tastes and smells. Also certain qualities of flesh, its firmness, warmth (realism undoubtedly), as with Titian’s Flora. This picture gives a sense of this flood of life: heightening one’s own (this seems very unaesthetic, perhaps it is). I confess to a wish to kiss—not to touch with fingers—the Flora’s throat. (270)

Lee experiences a physical reaction to colors and painted forms that she terms “bodily rapture,” and almost against her own will, confesses a series of ecstatic bodily sensations, including the desire to kiss the Flora, even while acknowledging that these “unaesthetic” admissions might not belong in her observational notes. 7 While reflecting at times that she feels only “platonically attracted” to some statues and paintings (322), Lee describes the Flora time and again through visibly erotic and sensual characterizations. She connects other works that she finds pleasurable, like the Capitoline Venus, to the Flora (273) and documents her experiences with Titian’s work during many visits to the Uffizi through language such as “Titian’s Flora takes me. Her glance, gesture, drapery, all drags one in” (289). While on some visits she claims, contradictorily, not to “feel any particular desire to touch or squeeze her,” she still delights in her own sensory reactions to the Flora’s form, noting “I try to go in by pleasure—tactical, thermic—at her flesh and skin, and the vague likeness to a friend I am very fond of. I get to like her—the silky fur quality of her hair, and her brows” (309). Such reflections thus emphasize a powerful presence of same-sex desire that winds throughout Lee’s discussion of aesthetic experience, a preoccupation which was evident even before her 1912 book. For instance, a letter she wrote in 1883, while composing Miss Brown, suggests Lee’s long-standing erotic attachment to beautiful aesthetic objects: “I saw at the Louvre a very beautiful & singular thing … It is a torso, half draped, of a Venus, found on the seashore at a place in Africa called Tripoli Vecchio—somewhere near Carthage, I presume—It has evidently been rolled for years & years in the surf, for it is all worn away, every line & curve softened, so that it looks like exquisitely soft and strange & creamy, hands, breast, & drapery all indicated clearly but washed by the sea into something soft, vague & lovely” (Gagel 423).

Beyond the erotic charge and “bodily rapture” that Lee experiences in her engagement with paintings and sculpture, the study of Einfühlung also afforded Lee with a justification for observing the living, breathing female body, not only its painted counterpart. According to Whitney Davis, “empathy in Lee’s sense is directed not only at transcendent artworks but also and primarily at people. One cannot empathetically grasp the artwork without corporeal awareness of one’s own body and the bodies of others” (182-83). In fact, one specific body, that of Kit Anstruther-Thomson herself, is the main focal point of Lee’s observations. As a result of her own inability to feel reactions to art as powerful as those Kit reported, Lee came to believe that her partner possessed a body particularly susceptible to artistic stimulation (Burdett 12). In fact, Lee argued that Anstruther-Thomson was uniquely worthy of observation because after “a long course of special training” she had succeeded in increasing “not only her powers of self-observation but also most probably the normally minute, nay, so to speak, microscopic and imperceptible bodily sensations accompanying the action of eye and attention in the realization of visible form” along with “sensations of altered respiration and circulation” (Beauty and Ugliness 25-26).

Consequently, these discussions center not only on visual engagement with material objects, but on a complex network of interpersonal perceptual experiences in which Lee would watch Anstruther-Thomson as Anstruther-Thomson gazed at a painting or sculpture, presumably experiencing sensations of desire alongside that empathetic mixing of self and other. As Lee and Anstruther-Thomson explain in their 1897 text, perception “of form” is a constant in our daily, waking lives. Unlike eating, drinking, or sleeping, desires which are dulled when satiated and then, for a period of time afterwards, no longer interesting, “the pleasure derivable from the perception of Form can continue with great constancy and unintermittence; even as we should expect to find if the pleasures due to Form were dependent on processes which, instead of being intermittent, like the processes of sleep, food … are as unintermittent as the processes of respiration and equilibrium” (551). The pleasure found in the constant perception of form throughout our daily lives then ebbs and flows like “respiration”; the erotic, rapturous charge of Einfühlung has no clear beginning, middle or end and the desire for continued contact does not “deaden” but rather “continue[s] with great constancy and unintermittence” (551). With the range of potential objects of same-sex desire extending beyond clearly reified sources into the realms of the inanimate and the abstract, this rapturous sensation is readily available through perception of a whole host of diverse materials and bodies, as long as we are willing to open our eyes to it.

Ultimately, despite their detailed engagement with scientific source material, Lee’s and Anstruther-Thomson’s scientific aspirations fell a bit short, a view late-century criticism acknowledged and one the current scholarship has continued. 8 Diana Maltz explains that Anstruther-Thomson’s physiological studies were far more cursory than Lee’s, and while Kit sometimes used scientific terminology in hopes such terms would “lend her writing credence,” she often used the terms incorrectly (220). Lee herself failed to develop what we could define as a proper scientific methodology because she limited her investigation to the bodies of only a few subjects, relying heavily on the physical reactions of Anstruther-Thomson and herself. Lee even confessed her awareness of her own status as outsider within the scientific field with a disclaimer in the 1912, full-length reworking of Beauty and Ugliness, writing:

My aesthetics will always be of the gallery and the studio, not of the laboratory. They will never achieve scientific certainty. They will be based on observation rather than on experiment; and they will remain for that reason, conjectural and suggestive. But just therefore they may, I venture to think, not only give satisfaction to the legitimate craving for philosophic speculation, but even afford to more thorough scientific investigators real or imaginary facts for their fruitful examination. (viii)

Unconcerned then with her lack of scientific training and methodology, Lee plunged ahead with her study in search of “conjectural and suggestive” data, rather than for the seemingly more objective findings of “the laboratory.” Lee’s playful characterization of her work as discovering “real or imaginary facts,” a phrase that challenges a notion of definitive truth or objective, factual information, is indicative of much of her aesthetic theory, which lingers in the spaces in between, caught somewhere in the middle of human and nonhuman, subject and object, reality and illusion.

Like her descriptions of ghostly forms, which dismiss any claim of objective material existence in favor of an argument for elevating the projections of one’s mind to the same level of importance as common material objects like hats and coats, Lee’s theories of empathy conflate what is materially present with what is produced as a result of subjective thoughts and perceptions, revealing them as one in the same.

Occult Sensations and Erotic Attachments

When read in the context of these aesthetic theories, visual experience in Miss Brown, whether centered on a beautiful body or an aesthetic object, takes on new significance, exposing a clear resonance between the perceptual experiences in the early novel and Lee’s later theorizations. Walter Hamlin, that representative of enervated aestheticism, enters the narrative in its first pages with a weakened connection between his internal life and the surrounding world. He lacks a muse and is devoid of artistic inspiration. Lee describes how beautiful features of the surrounding landscape seem to have “lost for him their emotional color, their imaginative luminousness” while previously “such things had soaked into him, dyed his mind with colour, saturated it with light instead of remaining, as now, so separate from him, so terribly external, that to perceive them required almost an effort” (I: 1). In this description, Lee hints that at the start of his career, Hamlin maintained an empathetic relationship with his material surroundings. Like Kit’s in the gallery, Hamlin’s body and mind were constantly “feeling themselves into” beautiful landscapes and other “such things,” which then “soaked,” “dyed,” and “saturated” him in return. Lee goes on to describe Walter’s early poetry—the brand of poetry for which he has now lost his inspiration—as a profusion of visual images, writing that “he had begun his poetical career with a quiet concentration of colour, physical and moral, which had made his earliest verses affect one like so many old church windows, deep flecks of jewel lustre set in quaint stiff little frames” (I: 2). But the Hamlin we meet at the start of the novel is no longer the creator of jewel-like, colorful verses that “affect one” like flickers of light, for “in poetry, and in his reality as a man, it struck him that he had little by little got paler and paler, colours turning gradually to tints, and tints to shadows, pleasure, pain, hope, despair all reduced gradually to a delicate penumbra, a diaphanous intellectual pallor” (I: 2). Through her opening passages, Lee reveals that Hamlin, drained of color and imagination, has been sapped of his ability to enact Einfühlung and interact empathetically with the material world. Generative aesthetic engagement for Lee is predicated on a deep connection between the external material object and the human viewer’s internal perception of it. As a result, Hamlin’s inability to connect with the visual landscape, and his failure to become infused with its “emotional color,” signals an immediate problem with his visual and emotive capacities.

But Hamlin soon finds this “diaphanous intellectual pallor,” which infects both his poetry and “reality as a man,” is tempered by a burst of inspiration in the form of Anne Brown, nursemaid to his friend Perry’s children, whom he meets while visiting his friend in Florence. In a heterosexual prefiguring of Lee’s later writings on Kit’s physical reactions to art, Hamlin stares at Anne during a performance of Rossini’s Semiramide early in the novel, “watching each movement of her hand and neck, as she devoured the performance with eyes and ears.” Lee tracks Anne’s bodily changes down to the smallest detail and notes these fluctuations in highly erotized language. As the opera reaches a tragic conclusion, Anne sits “resting her mass of iron-black hair on her hand, her other hand lying loosely on her knees. Her chest heaved under her lace mantilla, and her parted lips quivered” (I: 48). Given this scene’s connection of Hamlin with another obsessive observer of female bodily response, Vernon Lee herself, it should come as no surprise that Lee once confessed in a March 1884 letter that she feared she was “a sort of Walter Hamlin” (Gagel 516).

Beyond the aesthetic focus in Miss Brown, the occult also appears to offer Hamlin opportunities for connection between himself and disparate bodies and minds. Like Lee’s Einfühlung, spiritualism and mesmerism posited a theory of the self as radically open to the world, hinting that “we are not solely contained within the boundaries of the body” (Martin 24). Just as Lee describes the feeling of loss of self during moments of aesthetic engagement, Walter Hamlin experiences the same disruption of identity during mesmerism, explaining “I enjoy it … it’s like the first effects of opium or haschisch. One feels one’s self giving way, one’s soul sinking deliciously” (II:141). While holding hands with Hamlin at the séance, Sacha Elaguine, Miss Brown’s villainous femme-fatale, also claims she can feel the borders of her body falling away, saying “You can’t think of what a strange, delightful sensation I have at these moments … I seem to feel the whole current of your life streaming through me and mingling with mine. It is like an additional sense” (III: 5). While Anne Brown is impatient with these practices, believing them to be largely fraudulent and ridiculous, Lee still notes her heroine’s physical reactions and bodily sensations during moments when she comes in contact with the occult. When Edmund Lewis attempts to mesmerize Anne, for example, she feels powerful sensations of illness: “During his performance, as he fixed his green eyes upon her, and made passes with his flabby white fingers, Anne felt a loathing as if a slug were trailing over her, but she sat unaffected by Mr. Lewis’s will-power, and at last wearied out his patience” (II: 140). While this passage may claim that Anne is “unaffected,” we can see that she does in fact feel something: a sensation of an oozing slug creeping across her skin, as she registers Lewis’s attempt at mixing his consciousness with hers as a clear bodily violation.

As evidenced by this description, the relationship between medium and the mesmerist, like that of artist and muse, is colored by noticeably fraught power dynamics. In her investigation of nineteenth-century mesmerism, Alison Winter explains that “The power of looking and the relations of influence operating between the person looking and the thing being looked at were at the heart of [these occult] experiments” (31). The sustained eye contact, along with the scenes’ “mesmeric passes,” motions in which the mesmerist would run his hands “down the length of the body, extremely close but not touching the skin or clothing” (160), all signal a “suggestive intimacy” between the male mesmerist and the female medium, an intimacy that in Anne’s situation is deeply unwelcome (137). Anne even identifies the practice explicitly with a loss of will and control. As the narrator explains, “Anne loathed it: the triviality disgusted her, the giving of one’s will to another revolted her, and she could not understand how a woman could endure to be handled and breathed upon by a man like Lewis” (Miss Brown III: 5).

Despite her feelings of violation, Anne does in fact triumph over Lewis in this scene, rebuffing his attempts to enact mental contact and exposing the power struggle at the heart of this interplay between mesmerist and unwilling medium. When describing Lewis's rage at his failure to mesmerize Anne, Lee shows the “sensual” nature of his interest, claiming Lewis “felt how utterly all that kind of occult sensual fascination, which his pale mysterious face, his vermilion lips, his cat-like green eyes, his low droning voice … indubitably exercised over many women, how utterly it trickled off Anne” (II: 238-39). Lewis attempts to transform Anne into a spectacle, “the thing being looked at,” and initiate a type of heterosexual contact. Anne’s rejection of his attempts thereby constitutes a larger refusal of Lewis as an object of sexual interest, as Lewis’s masculine “occult sensual fascination” merely “trickle[s] off Anne” instead of penetrating or infusing her. After failing to successfully “magnetize” Anne, Lewis tries instead to exercise control over her physical form through sketching, drawing her likeness but “curiously distorting her expression” in the process (II: 141). The occult and the aesthetic thus converge once again here through shared representations of erotic sensation and a possessive sexualizing of female bodies and forms.

Just as Lee’s gallery observations are bound up in experiences of desire for Kit, these scenes in Miss Brown often stray away from heterosexual desire in favor of representations of same-sex attraction. Sacha, who develops her skills as a medium over the course of the novel, is arguably the central link between the occult and the bodily sensations of sexual desire. Through her depiction of Sacha, whom Lee saw as not unlike the period’s celebrity occultist Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, Lee suggests that susceptibility to spiritualism is, in fact, rooted in the physical and mental particularity of each subject, much like that talent for psychological aesthetics that allowed Anstruther-Thomson to feel such powerful reactions to art. 9 When a doctor is invited to one of Hamlin’s parties and notices Sacha, he remarks to Anne “I wonder whether [Sacha] is not a spiritualist—she looks like it … some sorts of temperaments are naturally inclined to [spiritualism], and … it reacts upon them” (II: 254). Just as Lee claims Kit possesses particular mental and physical faculties that allow her to successfully “feel herself into” art objects, the doctor argues that there might be something deep in Sacha’s makeup that “naturally incline[s]” her to spiritualism.

Lee even goes so far as to describe Sacha’s powerful sexual appeal, which ensnares both men and women, as a form of mesmerism several times throughout the text. Anne feels a strange experience of penetration in Sacha’s company, not unlike the sensations she felt while caught in Lewis’s mesmeric gaze: “… the presence of [Sacha] seemed to freeze her, like the contact of some clammy thing: it was as if the soul of Edmund Lewis had entered her body and had become more active” (III: 87). Anne is repeatedly described as aloof or icy in the presence of men, but when she is near Sacha, she not only feels, but experiences powerful, overwhelming sensation. As Psomiades has persuasively argued, Anne’s reactions to Sacha are consistently infused with this intense bodily feeling; Sacha’s gaze and touch cause Anne to feel hot, “clammy,” or suffocated (III: 60). 10 During their initial meeting, Sacha entreats Anne with a plea for touch, asking “Will you give me a kiss?” However, after she complies, Anne immediately experiences “a short of shudder [that] passed through her as her own lips touched that hot face, and grazed the light hair, which seemed to give out some faint Eastern perfume” (II: 190). Hamlin also feels this experience of connection, explaining that Sacha has “a sort of magnetic fascination” (II: 245). Sacha successfully seduces Hamlin late in the novel and her hold over him results in physical reactions that look like those of a mesmeric trance: he becomes passive, weak, and immobile, looking “as if there were in his face something, half physical, half spiritual, a vague, helpless half-stupefied look” (III: 77). Like the mesmerist Edward Lewis, much of Sacha’s power originates in the visual, once again highlighting the importance of sensory perception to this mysterious process of mixing self and other. Just as Anne calls attention to Lewis’s penetrating gaze, Hamlin reflects on Sacha’s: “she has strange eyes; one looks into them and finds she has merely drawn out one’s soul without showing her own” (II: 191). Through such allusions and parallels, Lee continually positions the occult within a network of erotic sensations, highlighting the visual similarities between the body of the passive medium and the body of the infatuated lover. 11

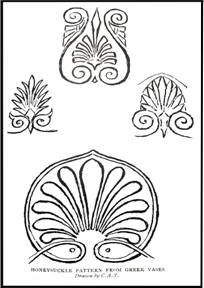

Similarly, through interactions between Hamlin and Lewis, Lee shows how mesmeric trances can enact homoerotic contact. While Anne, “prosaic and common-sense … impatient of the vulgar mysteriousness of modern magic,” is “insulted by the notion of surrender to the perfectly unintellectual will of another,” Hamlin rejoices in it (II: 140). In his susceptibility to mesmerism, Hamlin proves more passive and stereotypically feminine than Anne; he “surrender[s] to the …will” of another man and ensures Lewis gains “an undeniable influence” over him (II: 140, 124). As we can see from an image included in William Davey’s 1862 The Illustrated Practical Mesmerist (Figure 2), the optics of mesmerism, when exercised between a male mesmerist like Lewis and a male subject like Hamlin, can prove explicitly homoerotic. The two men in the illustration stare deeply into each other’s eyes, their gaze steady and unbroken. Their hands are entwined and their bodies are positioned in close proximity to one another, with their legs and feet almost touching. In fact, without any information identifying it as a mesmerist experiment, the image could easily be interpreted as a love scene.

Figure 2. From William Davey’s 1862 The Illustrated Practical Mesmerist: Curative and Scientific.

Whether it is looking into the eyes of a mesmerist or at a painting on a museum’s wall, Lee’s representations of visual perception in both occult and artistic spaces position the self as radically open to infiltration and expose the tenuous division of the subjective workings of the mind and so-called reality. In short, visual experience in Lee more than hints at a world full of contradictions and shifting identities. As Lee explains in her essay “On Friendship,” included in Althea (1894), “Is not our mind the collection of things outside us, sights, sounds, words—the thoughts and feelings of other folk … Where do I end, and you begin? Who can answer? We are not definite, distinct existences … we are for ever meeting, crossing, encroaching, living next one another, in one another, part of ourselves left behind in others, part of them become ourselves” (133). Perception is one of the central modes through which Lee can infuse her fictional and nonfictional texts with this understanding of reality, effectively dismantling traditional binarized categorizations of self and other and highlighting the changeability of identity. For if the inner self is constantly “meeting, crossing, encroaching” into the material spaces of the outside world, traveling into an aesthetic object or the seemingly discrete consciousness of another subject, identity is far from a stable, knowable category. Instead, the notion of self that emerges from Lee’s pages is a loose and hazy concept, forever fluctuating based on its changing surroundings, in constant danger of losing all form.

Anne Summers is a PhD Candidate and Instructor in the English department at Stony Brook University. Her research explores the relationship between visual perception, desire and materiality in the Victorian novel from the 1850s through the early 1900s.

Notes

1 One important exception is Kirsty Martin’s recent book Modernism and the Rhythms of Sympathy (2013) which offers an insightful discussion of Miss Brown’s engagement with Lee’s aesthetic theories, along with mention of their relation to the occult scenes in the novel. While Martin’s reading has certainly helped to inform my own, much of her focus is on empathy in Lee’s later fiction and the moral and political stakes of empathy and sympathy. My essay thus expands on Martin’s argument while offering a more extensive investigation of the relationship between the occult, visual perception, and psychological aesthetics in Miss Brown, specifically.

2

For a helpful explanation of Lee’s far-reaching and, at times, confused critique of aesthetic society see Vineta Colby’s chapter on Miss Brown.

3

Lee’s female characters are often based on common tropes, such as the femme fatale, in her effort to highlight the artificial and socially-constructed nature of these different “types” (Zorn 24). As Lee writes in “The Economic Dependence of Women,” the notion of “women,” outside the male construction of the word, is largely unknown: “…we do not really know what women are. Women, so to speak, as a natural product, as distinguished from women as a creation of men; for women, hitherto, have been as much a creation of men as the grafted fruit tree, the milch cow, or the gelding who spends six hours in pulling a carriage, and the rest of the twenty-four hours standing in the stable” (89).

4 Scholarship on women in the Pre-Raphaelite movement, such as work by Kimberly Wahl, emphasizes that the real-life movement was not as one-sided as Lee’s novel suggests (90). Elizabeth Siddal, the famous Pre-Raphaelite model and eventual wife of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, was both painter and muse. The Grosvenor Gallery often exhibited work by female artists. The movement was, therefore, more nuanced than Lee shows and its female members may have simultaneously experienced both objectification and opportunity for creative expression.

5 Morgan shows the close relationship between Pater’s and Lee and Anstruther-Thomson’s writings, arguing that the women use “the language of physiological aesthetics to answer Pater’s questions with brilliant, almost parodic literalness” (37).

6 In fact, in the 1912 version of Beauty and Ugliness, Lee explains that at the time of her earlier collaboration with Anstruther-Thomson, neither woman had any knowledge of the theory of Einfühlung (88).

7 Dennis Denisoff points out the “sensuality” of Lee’s descriptions of perceptual experience and the “erotics of her notion of empathy,” calling it “nothing less than an orgasmic submersion into a flowing throbbing rapture” (101).

8 While Whitney Davis claims that the short primer The Beautiful was actually quite popular (176), The New York Times had called Beauty and Ugliness “simply a terrible book,” critiquing its “long, involved sentences, long scientific terms, queerly inverted thoughts, French words and Latin and German, [which] all hammer a tone’s cerebral properties with unquenchable vehemence” (28 Apr. 1912). This reaction is not unique to the early twentieth century. Morgan, for example, calls the text “an unfortunately ponderous and disorganized book” (38). As Burdett has noted, other Lee scholars,including Diana Maltz, Vineta Colby, and Angela Leighton, while offering persuasive interpretations of Lee’s aesthetic theories, often approach the topic with a touch of sarcasm. Maltz calls the gallery experiments “the stuff of decadent high comedy” (213); Colby contends that the obsessive detail of Lee’s records “at times … borders on the ludicrous” (157); Leighton disputes the scientific validity of the findings, arguing that “As psychology, this is probably laughable” (104).

9 In a letter to her partner Mary Robinson in November 1884, Lee wrote “I am also interested in reading Sinnet’s Occult World, as a study of what credulity & conceit can together achieve. It is curious that an Englishman can’t conceive that a Russian woman may be most respectable in all her connexions & life, & yet be the most arrant imposter from sheer love of imposture & excitement; Mme Blavatsky is, I should think, a mere reedition, much augmented, of the lady from whom I took the mock persecution in Miss Brown” (Gage l597).

10 See Beauty’s Body for an extensive discussion of the role of same-sex attraction in Anne Brown’s relationship with Sacha.

11 In an 1881 letter to Mary Robinson, Lee makes an explicit connection between romantic attachment and supernatural presence, noting “I think when one loves as I love you, one can scarcely ever be quite alone: there is always a sort of phantom companion, to whom one shows everything, whose words & looks one almost hears & sees” (Gagel 335).

Works Cited

Burdett, Carolyn. “‘The Subjective Inside Us Can Turn into the Objective Outside’: Vernon

Lee’s Psychological Aesthetics.” 19: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century, vol. 12, 2011, pp. 1-31. www.19.bbk.ac.uk/articles/10.16995/ntn.610/. Accessed 15 February 2017.

Colby, Vineta. Vernon Lee: A Literary Biography. U of Virginia P, 2003.

Davey, William. The Illustrated Practical Mesmerist: Curative and Scientific. 3rd ed.,

1862. archive.org/details/illustratedpract00dave. Accessed 15 June 2017.

Davis, Whitney. Queer Beauty: Sexuality and Aesthetics from Winckelmann to Freud and

Beyond. Columbia UP, 2010.

Denisoff, Dennis. Sexual Visuality from Literature to Film, 1850- 1950. Palgrave Macmillan, 2004.

Fredeman, William E., editor. The Correspondence of Dante Gabriel Rossetti: The Chelsea Years, 1863-1872, vol. II, D.S. Brewer, 2004.

Gagel, Amanda, editor. Selected Letters of Vernon Lee 1856-1935, vol. 1, Routledge, 2017.

Gomel, Elaine. “‘Spirits in the Material World’: Spiritualism and Identity in the Fin De Siècle.” Victorian Literature and Culture, vol. 35, no. 1, 2007, pp. 189–213. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40347131. Accessed 15 February 2017.

Gordon, Avery. Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination. U of Minnesota P, 1997.

Lee, Vernon. Althea: A Second Book of Dialogues on Aspirations and Duties. Osgood,

McIlvaine, 1894. HathiTrust Digital Library, catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000247706. Accessed 15 February 2017.

---. The Beautiful: An Introduction to Psychological Aesthetics. Cambridge UP, 1913.

archive.org/details/beautifulintrodu00leevuoft. Accessed 15 January 2017.

---. Belcaro: Being Essays on Sundry Aesthetical Questions. T. Fisher Unwin, 1887.

archive.org/details/belcarobeingess00leegoog. Accessed 15 January 2017.

---. “Comparative Aesthetics.” Contemporary Review, vol. 38, Aug. 1880, pp. 300–26.

books.google.com/books?id=VMw1AQAAMAAJ&dq. Accessed 15 January 2017.

---. “The Economic Dependence of Women.” North American, vol. 175, July 1902, pp. 71-90.

JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/25119274?. Accessed 20 February 2017.

---. “Faustus and Helena: Notes on the Supernatural in Art.” The Cornhill Magazine, vol. 42, 1880, pp. 212-28. books.google.com/books?id=yAjSAAAAMAAJ&q. Accessed 15 February 2017.

---. Miss Brown: A Novel. William Blackwood, 1884. 3 vols.

---. Renaissance Fancies and Studies: A Sequel to Euphorion. Smith, Elder, 1895. archive.org/details/renaissancefanci00leevuoft15. Accessed January 2017.

Lee, Vernon and Clementina Anstruther-Thomson. “Beauty and Ugliness.” The Contemporary Review, 1 July 1897, pp. 544-69. books.google.com/books?id=

CjgeAQAAIAAJ&q. Accessed 15 February 2017.

---. Beauty and Ugliness and Other Studies in Psychological Aesthetics. John Lane, 1912.

Leighton, Angela. On Form: Poetry, Aestheticism and the Legacy of a Word. Oxford UP, 2007.

Maltz, Diana. “Engaging ‘Delicate Brains’: From Working-Class Enculturation to Upper- Class

Lesbian Liberation in Vernon Lee and Kit Anstruther-Thomson’s Psychological Aesthetics.” Women and British Aestheticism, edited by Talia Schaffer and Kathy Alexis Psomiades, U of Virginia P, 1999, pp. 211–29.

Martin, Kirsty. Modernism and the Rhythms of Sympathy: VernonLee, Virginia Woolf and D.H

Lawrence. Oxford UP, 2013.

Morgan, Benjamin. “Critical Empathy: Vernon Lee’s Aesthetics and the Origins of Close

Reading.” Victorian Studies, vol. 55, no.1, 2012, pp. 31-56. JSTOR,

www.jstor.org/stable/10.2979/victorianstudies.55.1.31. Accessed 15 February

2017.

Pater, Walter. The Renaissance: Studies in Art and Poetry. 1877. Macmillan, 1910, www.gutenberg.org/files/2398/2398-h/2398. Accessed 15 Dec 2016.

Psomiades, Kathy. Beauty’s Body: Femininity and Representation in British Aestheticism.

Stanford UP, 1997.

---. “‘Still Burning from This Strangling Embrace’: Vernon Lee on Desire and Aesthetics.” Victorian Sexual Dissidence, edited by Richard Dellamora, U of Chicago P, 1999, pp.21-42.

Wahl, Kimberly. Dressed as in a Painting: Women and British Aestheticism in an Age of Reform. U of New Hampshire P, 2013.

“What is Beauty? Vernon Lee Seeks an Answer in Distinctly Verbose Terms.” The New York Times. 28 April 1912, search.proquest.com/docview/97233042?accountid=14172.

Accessed 15 December 2016.

Winter, Alison. Mesmerized: Powers of Mind in Victorian Britain. U of Chicago P, 1998.

Zorn, Christa. Vernon Lee: Aesthetics, History, and the Victorian Female Intellectual.

Ohio State UP, 2003. |