Latchkey Home Book Reviews Essays Conference News Featured New Women

New Women: Who's Who GalleryThe Whine Cellar

Teaching Resources Bibliography

Contact us

|

|

Imagining the Neue Frau: The Modern Woman in the Weimar Republic Illustrated Press

By Jennifer Lynn.

Introduction

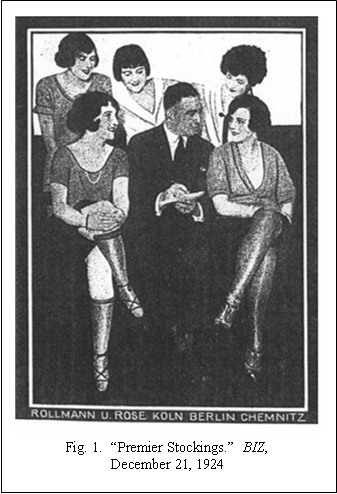

In December 1924, the popular German magazine Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung (BIZ) printed an image of the Neue Frau or New Woman (fig. 1). This archetypal portrait of the female white-collar worker, in an advertisement for stockings, helped define the economically independent woman of 1920s. The “boss” is encircled by five attentive young women. Adorned with short, dark hair and garbed in stylish clothing, the women look directly at him. The two women in front, wearing short skirts, are not ashamed to show their stockings, while the woman on the right exchanges a personal look with her boss. The stylish bubikopf and fashionable clothing are signifiers of the Neue Frau. The ad is typical for Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung, the quintessential middle-class magazine, in that a woman’s job performance does not rest upon her professional skills. The performance, in front of her coworkers and her supervisor, centers instead upon her appearance.

The advertisement also harkens to the cultural belief that the Neue Frau used the workplace to attract a man for marriage. During the Weimar Republic, which spanned from 1919 to 1933, the commercialised image of the Neue Frau (sometimes referred to as the Moderne Frau, or modern woman) focused on a young, single female, who earned her own money, wore stylish short dresses, chopped off her hair, used cosmetics, smoked, and spent her leisure time going to the cinema or dancing. She pursued economic and sexual independence, loved fashion and admired movie stars. Her paid work as a secretary or shop girl would provide a small income for those clothes and entertainments. When she dreamed about her future, she hoped to eventually meet a man with an income that would allow her to quit her job and stay home to care for her family. As studies have shown, this complex and often contradictory image of the Neue Frau became the symbol par excellence of the new, consumer-driven Weimar mass culture and was propagated not only by mass-media like the illustrated press and movies, but also by popular art, contemporary fiction, and the advertisement section in conventional newspapers. 1

However, the Neue Frau was not just a phenomenon of the middle-class, commercial press. Throughout the Weimar Republic, the issue of female modernity and related policies became an important political subject for all parties across the spectrum, including the Communist Party (KPD), the Social Democratic Party (SPD), and the National Socialist or Nazi Party (NSDAP). These groups criticized, modified and adapted the Neue Frau image with the aim of constructing competing versions of modern femininity in accordance with their particular economic, social and political agenda. Their attempts to define and contest “modernity” were inseparable from efforts to address welfare and family policies, the gendered division of labour in the family, society and the economy, the rationalisation of reproduction and sex reform, or women’s political participation. The modern woman and her representations were not at all monolithic in concept or in reality. The many visual and textual representations of the highly contested Neue Frau directly relate to the ambiguities, ambivalences and paradoxes of historical constructions of modernity. 2

Much of the current scholarship on the image of the Neue Frau concentrates on the iconic representations found during the Weimar Republic. My work questions their depiction of a relatively coherent representation of female modernity and focuses on the variety of competing images of the Neue or Moderne Frau. 3 In this paper I concentrate on depictions of the female white-collar worker in mass-circulated illustrated magazines published during the interwar years. I ask why was this image important? How do the particular representations relate to the realities of post-war politics and paid labour for women? How and why did magazines debate the meaning and reality of white-collar work? It was, I conclude, ultimately, the visual image of the Neue Frau that became so crucial to disseminating the ideas of female modernity.

The illustrated magazine became extremely popular in post-WWI Germany due to technological advancements and inexpensive printing costs which allowed for an extensive distribution. Although other forms of entertainment were available, magazines were cheap and reached a broad audience. 4 The variety of publications meant that images of the Neue Frau could be constructed within different political and social contexts, exemplifying the modern nature of the medium itself, and reach a highly diverse readership. These publications include the Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung, Germany’s first mass-commercial illustrated publication which was founded in 1890. Its liberal orientation appealed to a mainly middle-class audience; by the 1920s BIZ’s annual circulation was over two million copies, a steady record that extended into the next decade. The communist periodicals, Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung (Workers Illustrated Magazine, AIZ) and Der Weg der Frau (Women’s Way), were also widely distributed. The AIZ had a press run of 200,000 in 1925 and 300,000 in 1933, appearing at first biweekly before its change to a weekly between 1927 and 1933 when the Nazi Party closed its Berlin offices. The publication was edited by the writer and activist Lilly Becher, who had experience working on different communist publications in the early 1920s. In 1933, Marianne Gundermann, a committed leader for women’s issues, began editing Der Weg der Frau. This monthly women’s magazine was published once a month, until the Nazis shut it down in 1933. Between 1924 and 1933, the SPD published Frauenwelt (Women’s World), an illustrated magazine for women and edited by Toni Sender, an active member of the Social Democratic Party and member of the Reichstag from 1920-1933. In its first quarter, Frauenwelt amassed 67,000 subscribers; by 1926, it had 100,000 readers with forty to sixty percent of the SPD’s female party member subscribers. Like Weg der Frau, Frauenwelt aimed for an audience beyond the women in the party, a goal met perhaps when its circulation peaked at 120,000 in 1933. Max Amann and Heinrich Hoffman, members of the National Socialist German Workers' Party, founded the NSDAP’s own illustrated magazine, the Illustrierte Beobachter (Illustrated Observer, IB) in 1926 under the Nazi publishing house Franz Eher Verlag. It served their party’s members and, in its first year, reached a modest 50,000 copies. By the end of the 1920s the Illustrierte Beobachter reached over 300,000 readers, a number that the Nazi dailies increased to about 3.2 million, and it continued to be a popular publication during the Third Reich.

While these texts must be understood in the complex historical context in which they were produced and read, a point I address below, the theoretical and methodological approach of “intermediality” augments my examination of the relationship between visual and textual images (Wagner 17). The illustrated magazine is unique in its function to inform, entertain, persuade and explain by using a combination of visual images and text. Unlike films where images flicker across the screen, or novels which construct a “verbal picture,” illustrated magazines offer a unique forum that allows the reader to extrapolate meaning by both “seeing” and “reading.” As scholars and critics have long noted, photography was laden with ties to the scientific understanding of the world, one that was “objective,” a reality filtered through a lens and then presented to the public by a magazine’s editors. Media scholar Hanno Hardt argues, “Photographs are assigned the power to establish the real conditions of society, either in the form of middle-class conceptions of tradition and survival or in the provocative style of social criticism, with its attacks on the social and political establishment” (10). The camera supplied the means to define a seemingly unprejudiced “truth,” and the perspective of “truth” was formed by both the individual taking the photograph and the publication’s placement of the photograph in its publication.

Thus, analysing this particular type of visual evidence depends on recognizing editorial choices, explicating the intermedial relationships, and identifying the aesthetics in photographic and graphic conventions, just as examining Weimar Germany’s political and economic landscapes lets us fully understand the debates surrounding the Neue Frau and her representations in the illustrated press. The following sections will explore the position of women in post-World War I Germany, the development and increase of female white-collar work, and finally, the variety of visual and textual images of the female-white collar worker the illustrated press promoted.

The Post-World War I Landscape

The First World War called into question some of the basic assumptions of the gender order. Women contributed to the war effort through paid work and supported the war by taking on jobs in war welfare. As Red Cross nurses or even military auxiliaries, they provided material and moral support to their nation. 5 Women’s demands for the vote were fulfilled with the establishment of the Weimar Republic. But, the revolutionary fervour in Germany and the tensions related to the founding of the republic also included demobilisation laws that required women to return home from the workforce. 6 Implicit in all arguments was the fear that a damaged nation and a declining birthrate, alongside the “emancipated” woman, did not bode well for the future of the nation. Regardless of any group’s previous opposition to female suffrage, however, they all attempted campaigns for women’s votes. Julia Sneeringer has argued that all of the political parties of the Weimar Republic shared basic assumptions about a gender-specific division of labour in politics and the essential maternal role of women. Almost all party propaganda portrayed women “as ultimately capable of only political action consistent with ‘female nature’ . . . while simultaneously discouraging them from deploying that femininity in ways that could seriously challenge the status quo” (15).

At the Weimar Republic’s establishment, women’s participation in elections seemed promising with nearly 80 percent of all eligible female voters participating in the first elections in 1919 (Bridenthal 35). The vote, ideally, “would lead . . . to legal reforms, widespread social legislation, wage equalization, improved protection for women workers, and increased educational opportunities for women and girls” (35). Many women joined a political party, especially the Social Democratic Party, and, in 1919 and 1920, the trade unions as a response to the political changes and the equality the Weimar constitution seemed to promise them. However, because many men and women active in politics shared the belief of the party leaders that the natural maternal “female character” would contribute to the betterment of society and supported the “equal but different” approach to female emancipation, women participating in party politics and parliaments remained stuck in specific “feminine” areas of politics like education, family health, and welfare. Furthermore, many male members of parties and trade unions “worked increasingly to narrow women’s space in the political arena,” regarding politics as a “men’s matter” and resisting working with or competing against women in politics (Davis, “Personal is the Political,” 116). As historians have emphasized, “despite the rhetoric about women’s emancipation, patriarchal ideology continued to dominate all institutions of German economic and political life” throughout the Weimar Republic (Bridenthal 34-35).

Consequently, the gains for women’s equality in politics, the economy and society remained unsatisfactory. Many women who had joined a party or the trade unions in the early Weimar Republic soon left these male-dominated organisations. If they became active in politics, they did so on a local level, and worked in self-help networks, consumer, children’s and youth or welfare organisations, or advocated for the rising sex reform movement. 7 The lack of real change for women was symbolised by the decreasing number of women delegates in the Reichstag, which, in turn, may have reinforced women’s perception of politics as a “men’s matter.” In addition, aggressive rhetoric in the heated political debates and the street violence between the Nazis and their political opponents in the early 1930s may have motivated women to withdraw completely from politics or to support one of the more Christian or national-conservative parties that promoted women’s roles as wives and mothers as a return to the gender and social order of the past (Bridenthal 44). During the 1920s, women experienced a great divide between the political rhetoric of the parties – especially of the left – which called for women’s full equality in politics, society and economy, and their practices that often silenced female voices. Although women’s magazines like the KPD’s Weg der Frau and the SPD’s Frauenwelt included coverage of women involved in feminist activism, the illustrated press rarely focused on images of women elected to the Reichstag or other governmental positions.

After World War I, the influx of images of the Neue Frau the mass media disseminated increased the perception, especially in the conservative milieu, that women were out of control. They were “misbehaving,” rejecting their natural duties of mothers and wives, and pursuing extravagant pleasures and entertainment rather than contributing to the nation’s improvement. Birthe Kundrus has noted, “In the war years and after, it was the possibility of an economically, socially, politically and sexually independent woman that so strongly captured the imagination of contemporaries” (164). Solutions to assuage anxiety included continuous attempts to re-domesticate the female war worker. The demobilisation policy, media endorsement of women’s role in the domestic sphere, support for the public education of girls and women, formulating the early stages of a welfare state were all attempts to return to “normalcy” and to repair a population decimated by war.

Yet, reestablishing the gender order (and thus society in general) did not necessarily mean returning to an imaginary past. On the one hand, clearly delineated gender roles for men and women via gender-specific tasks in the “public” and “private” spheres signaled stabilisation. On the other hand, new types of the Neue Frau, who embraced the symbols of modernity, created a landscape in which modernity and assumptions about conventional gender roles were not always mutually exclusive. To be sure, some versions of the Neue Frau propagated in the mass media that depicted her as a self-assured, sexually independent urban consumer drew fire from both the far left’s and the far right’s publications. The figure of the female white-collar worker became a particular lightning rod for politicised rhetoric related to the burdens and experiences of women engaged in paid labour.

The Perception of Female Work in Shops and Offices

The expansion of white-collar work became one factor that pushed the construction of the Neue Frau into the cultural imagination of post-World War I Germany. The increased number of white-collar workers, a new phenomenon which linked shop assistants and office workers in the expanded bureaucratic administration and service sectors, assisted in the rise of the Neue Frau image. Historical narratives of Weimar Germany had previously interpreted this development of the labour market as a step towards the emancipation of women. 8 However, in the 1980s, feminist scholars began to re-examine the established notion that women flooded the labour market after World War I. By reevaluating statistical data and analysing labour market structures, Ute Daniel, for instance, and other feminist historians have revealed that women did not enter the labour force en masse during and after the First World War. Rather, the change occurred between and inside the sectors of the economy where women were working already. Women were simply more visible in “male” jobs during the war and increasingly in non-factory jobs (shops and offices) after the war. Susanne Rouette argues that although conventional, gender specific hierarchies in society had loosened during the First World War and social-democracy rhetoric had espoused equal rights for men and women, the post-war demobilisation policy reinstated the traditional gender hierarchy in the workforce. Germany’s defeat in the war, the German revolution of 1818-1819, inflation and the high instability of everyday working conditions led the federal government and the governments of the Länder, the federal states, to pursue policies that fostered reestablishing conventional gender hierarchies in the economy and society and within the family. Their aim was to provide “security” and “normality” in the economic social order (Rouette 182), and this “normality” necessitated the return to a rigidly gender-segregated labour market dependent on cheap female work in offices and shops.

The expansion of administration and services since the late nineteenth century required a workforce with new skills, including typing and stenography. Young women, who entered the labour market before and during the First World War, had the necessary skills. Clerks, secretaries, typists and shop girls made up the majority of the female white-collar working class. For these women, jobs as an office clerk or shop assistant were one step above factory work, since the working conditions were better and the salaries slightly higher. Because these female employees would have frequent contact with the public, especially in department stores where they needed to “sell” goods through their femininity, job qualifications included youth, beauty and a keen fashion sense (Frevert, Women in German 80-81). In 1925 two-thirds of female white-collar workers were under the age of 25 and almost all of them were single (179). Before the war, female clerical workers came mostly from a middle-class background, but afterward, and as the labour market hungered for more commercial staff, white-collar work offered a promise of rising in social status to a new generation of working-class girls (180-81; Hagemann, “Ausbildung”). This potential, however, did not negate the realities of the gender-segregated labour market. As Frevert explains,

Industry’s enormous demand for commercial and business staff, which had taken root in the late nineteenth century, was related to a process which divided standardised and mechanised work functions in a way that was far from gender neutral: women were given the most routine and simple tasks, particularly the operation of new office machines . . . While men saw it as an affront to their dignity if they had to stoop so low as to become typists, women seem to be blessed with a certain aptitude for the keyboard; digital suppleness acquired through playing the piano proved to be of practical value here (Women in German 178).

In 1925 there were almost one-and-a-half million female white-collar workers, three times more than there had been 1907, an increase of 5 to 12.6 percent of all women in paid work (177). The more perfunctory, mechanical, and repetitive work required fewer qualifications and paid less than that for men. As Frevert notes, although the role of a shop assistant or secretary seemed to provide a more privileged life, most young women office clerks and assistants lived below the poverty line (183). Nonetheless, and despite the inequities with similar employments for men, young women perceived their jobs in offices and shops as a step upwards, especially when compared to work for women in factories, on farms and in domestic service. The media’s construction and promulgation of the female white-collar worker fostered hope for the majority of young women wishing to enter that realm of paid employment despite the market’s continued segregation along the lines of gender.

The Neue Frau as the White-Collar Worker

Representations of female-white collar work in the Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung emphasized youth and beauty, primarily through advertisements, presenting a one-dimensional and stereotyped Neue Frau who was, above all, a consumer. In contrast, articles and pictures in the communist publications Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung and Der Weg der Frau critiqued the portrayals in films and popular novels to contrast the “fantasy” in media with the reality in the everyday life for these women. Der Weg der Frau in particular focused on real working conditions for white-collar workers in an attempt to make women more class conscious. Although communist publications vehemently opposed the woman office worker’s glamorized representation, the broader mass media made it impossible to ignore the image’s appeal.

Toward the end of the 1920s, the Social Democratic women’s magazine Frauenwelt included several articles that addressed the unrealistic expectations for female white-collar workers, but focused more on career opportunities for women in different sectors of the labour force, such as teaching, nursing and social work. From the late 1920s and into the early 1930s, Illustrierte Beobachter’s virtual neglect of representations of women in paid work speaks to the magazine’s marginalisation of women and an overall dismissive attitude toward Nazi female party members, who were mainly the wives of male party members. The Nazi press rarely printed articles for women, but did address the image of the white-collar worker within the context of mass unemployment during the Great Depression.

The relationship between paid work and the consumer-orientated Neue Frau in the Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung is highlighted by the advertisements in the magazine rather than in its editorial content. The advertisements targeted a young female readership with an expendable income, accentuating women’s role in the labour force solely via the power of her pocketbook. Like her counterparts in the period’s popular films and novels, this female consumer symbolised the Neue Frau. Authors and directors often placed her in her workspace as if to identify her with her employment, but working-conditions and wages were not the main topic. Rather, these narrative forms, like the magazine advertisements, made the Neue Frau’s appearance and relationships with the men around her the central importance. 9

Cosmetic, clothing and perfume industries targeted the secretary, typist or shop girl as the primary consumer. The typist or secretary in the advertisements is always young and attractive. In Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung’s June 2, 1929 issue, an advertisement for Kölnisch Water Lavender-Orange shows a woman seated behind a typewriter, holding a bottle of perfume, as her boss leans casually across her desk (fig. 2). Evidently, he is quite interested in what she has to say concerning the refreshing drops of lavender-orange perfume. “Good looks despite a stressful job!” the ad declares, signifying the importance of feminine appearance in the office. The descriptive text acknowledges the possibly realistic working conditions, such as “poor ventilation” and crowded space. These are problems the product can solve: the perfume promises to sooth the nerves and guarantees revived productivity. Yet, the visual content accentuates the woman’s male supervisor and the bold headline trumpets “good looks.” Efficiency and a calm manner take second place to the woman’s appearance. The most important characteristic for a female typist is her appearance, particularly in front of her boss.

|

Fig. 2. “Good looks despite a stressful job!” (author’s translation). BIZ, June 2, 1929

“A stressful job, especially in a room with poor ventilation and full of people makes you prematurely tired. This you can prevent! With a few drops of Kölnisch Water Lavender-Orange on your tissue deeply inhaled or on the forehead and behind the earlobes… provides for instant, visible relaxation. You will immediately feel the efficient, exquisite, revitalizing scent – that of a dewy blossom. Your eyes will be brighter, the nerves fresh and your resilience will return. Use it several times a day!”

|

Advertisements in the Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung for hand lotion and perfume regularly depicted women at work. The advertisements are similar in form, each a half-page and urging “typists, secretaries and stenographers” to buy products that would, for instance, ensure “charming and soft hands,” as one in the September 30, 1929 issue coaxed. “Hind’s Honey Cream” keeps the typist’s skin “soft and smooth” notes another ad that depicts the “typing pool” (BIZ, February 1929). While three short-haired women dutifully type away, one woman rests her chin on her hand. She sits in front of a stack of files, holds a pencil, and gazes at the viewer. Ads such as these both emphasise female employment and modern “feminized” office equipment like typewriters, but insist that a woman’s essential nature can be found in a jar of hand cream. “Why would you age early, if you can, through the use of Matt-Cream and Cold Cream stay young?” asks an ad published the year before in the February 24, 1928 issue. Here, a woman holds a jar of cold cream and points to the label, while two of her co-workers look on eagerly, one of them sitting on the desk, leaning in to listen. Maintaining one’s youthful skin with brand-name products seems the way to find and to keep a job. In an ad published in the April 24, 1928 issue, a young woman wearing a jacket and decorative tie sits behind a desk, and writes on a notepad. “The working woman knows which assets a young soft-skinned complexion displays,” the text explains. This advertisement, which is for Palmolive soap, notes that “the most beautiful film and stage stars use Palmolive . . . because other soaps are too harsh.” Here, the ad directly links the female office-worker to the glamourous women from the theatre and the movies. The office is her “stage,” where a working woman embraces the glamour and beauty of the cinema, all within the confines of her workplace.

These representations of female office workers allude to the Neue Frau’s sexuality. The Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung presents its readers with a discourse concerning female white-collar workers as only young, beautiful women who attract male authority and who must preserve their youth. For example, in the Kölnisch Water Lavender-Orange advertisement, the woman draws her male companion’s interest via her femininity and he assumes the dominant position. The male supervisor in figure 1’s stocking ad with which I opened my essay is literally and figuratively the center of attention. In these advertisements, the Neue Frau is an object on display at work. Her “productivity” is enhanced by what she wears and what perfume she uses, not by her intellectual abilities. She signifies an alluring combination of youthful beauty and sexuality found not only in Germany’s nightclubs, theatres or dancehalls but in the realm of the workplace. She is the fantasy typist or shop girl, depicted both as commodity and the idealised purchaser of consumer goods.

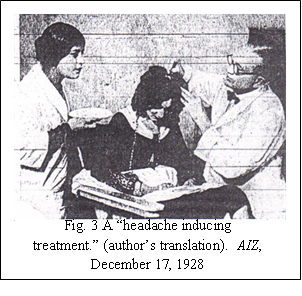

In contrast to Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung’s veneration of a glorified female employee, the communist Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung and Der Weg der Frau challenged the links between expectations of female beauty and youth and the image of women white-collar workers. Their critique intensified toward the end of the Weimar Republic when films and novels about the female-white collar worker became increasingly popular (Kosta, “Unruly Daughters,” 276). 10 An article in the December 17, 1928 issue of the Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung for example, admonished the bourgeois obsession with youth and beauty and its connection with white-collar work. “All for beauty,” reads its headline. Five photographs and one illustration document what young women will go through to remain young and attractive. The article begins by stating that most working-women, like “textile workers work nine or ten hours a day, and when the work in the factory is over, then begins the housework,” for both married and single women. Under these conditions it is very difficult for them to look young and beautiful for long. These are the “working and living conditions for the majority of women, which get worse in the case of unemployment or illness.” The article also emphasises that the female white-collar workers, “if they are not so pretty or modern,” have a difficult time finding work because they must maintain a specific appearance, to be a “free advertisement for the firm.”

Criticising women who “dream of being slim” the Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung included photographs of the latest beauty techniques. A woman has her face and neck massaged, because “one can, through this paraffin mask, stay ‘young and beautiful.’” Another photograph shows a woman lounging on a bed, “wrapped in a paraffin binding” in order to gain an “elegant and slim” body. In another, a serious looking man, in a white lab coat, dyes a “rich woman’s hair”; however, it is a “headache inducing treatment” (fig. 3) and the article calculates daily beauty routines in terms of time wasted and money spent.

Criticising women who “dream of being slim” the Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung included photographs of the latest beauty techniques. A woman has her face and neck massaged, because “one can, through this paraffin mask, stay ‘young and beautiful.’” Another photograph shows a woman lounging on a bed, “wrapped in a paraffin binding” in order to gain an “elegant and slim” body. In another, a serious looking man, in a white lab coat, dyes a “rich woman’s hair”; however, it is a “headache inducing treatment” (fig. 3) and the article calculates daily beauty routines in terms of time wasted and money spent.

Another article published in the February 1928 issue concentrates on a young middle-class female and asks, “What does a girl need for getting dressed?” While the previous examples focus on the physical “transformation” through beauty regimes or the more radical cosmetic surgery, this article examines clothing as a symbolic marker of class and the Neue Frau. Included on the page is a smaller and separate commentary entitled “U.S. Girl needs 600 Dollars for Clothes,” binding the modern American woman and her capitalistic gluttony for consumer goods to the situation for German women white-collar workers. Beneath a photo of eight pairs of neatly displayed shoes, a caption details, “The shoe collection of the ‘lady’ is so big—the working woman hardly has a second pair to alternate,” while one beside a photograph of a stylish young woman asks, “does the worker or proletarian housewife have time or money to look so nice as this young woman?” The article reassures that for just 20 marks, a poor, pretty girl can have a decent wardrobe that includes stockings, a hat, blouse, skirt, dress, coat, handbag and one pair of shoes. For the “majority of women who must create and maintain a pretty look for an office job,” patterns for home-made garments and inexpensive ready-made clothes were available. Thus, the problem for the Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung is not a woman’s desire for or need to adopt new fashion trends so to present herself at work in a stylish manner, but rather, the middle-class values that applaud rampant indulgence and the workplace demands employers imposed on their female employees.

Even without actual images, articles could conjure a colourful picture of a woman on the hunt for work and continue those high expectations white-collar work had for women’s appearance. The title in a September 1928 article in Frauenwelt reads, “Do you know what it is like . . . when you apply for a position as a private secretary?” Directly addressing the female reader, the anonymous author writes, “You read in the newspaper: General director of a textile warehouse searching for a private secretary, with speedy shorthand … who knows French and English . . . You apply, you wait and you get an interview.” The author emphasises the pains the young woman takes with her appearance, knowing it to be a crucial component of the interview. “You wear your best clothes,” the writer notes, and assume your best posture. The rest of the article is a play-by-play narrative of “your” experience. On the way to the interview “you are thinking in the back of your mind about the rent that is due tomorrow . . . and you hope to earn 300 marks a month at this new job,” emphasising the need to make ends meet. As you enter the waiting room you see “twenty blond and dark-haired girls, all in gray, blue and black suits,” all of whom “have the skills.” Suddenly, a woman who just finished the interview walks into the room with “triumph in her eyes” and you hear the announcement that the job has been filled. You leave disappointed and tomorrow the rent is due. Thus, the article ends with a frank warning to young women who hope to become a private secretary.

However, unlike the communist Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung and Der Weg der Frau, Frauenwelt did not present white-collar work, on the whole, as the problematic that caused the far left such concern. Rather it gave its female audience articles and pictures that showed different options for women’s work and debated the challenges of the double burden in combining both paid work in the labour market and unpaid home and care work. Frauenwelt also offered advice for a fashionable but affordable wardrobe. More significantly, the social-democratic Frauenwelt avoided using the radical discourse of cultural and social criticism the communist magazines employed in distancing themselves from the more moderate politics of the Social Democratic Party.

The genre of the “office film” and similarly-themed novels presented a perfect target for the Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung and Der Weg der Frau because they could criticise the role of commercial mass-media and condemn middle-class cultural values and consumer practices while offering solutions rooted in their belief that socialist revolution would bring political, social, and economic change. Within the context of the period’s economic crisis these criticisms of “bourgeoisie” culture took on even greater resonance as the magazines continually emphasised the gulf between representations in the media and the daily hardships of poor working conditions, unemployment and the struggle of working class families to make ends meet.

In Der Weg der Frau’s second issue in 1931, “The False Film Ideal” criticised very popular films like the 1931 musical comedy Die Privatsekretärin (The Private Secretary) directed by Wilhelm Thiele, in which a typist marries her boss. This type of movie, the magazine observes, depicts only a “dream.” The review complained that “very few proletarian women know the cinematic masterpieces of directors like Eisenstein, Pudovkin, Charlie Chaplin, Stroheim or Joseph von Sternberg,” thus gently chastising their readers who indulge in bourgeois films and offering alternative, more rigorous viewing suggestions. The short review included an uncaptioned picture of the “false” film ideal: a young woman, presumably the “private secretary, in the arms of a handsome man. In February 1932, another article in Der Weg der Frau criticised representations of women’s everyday work on the “silver screen.” The female white-collar workers in the movies have soft hands and play sports to maintain a trim figure. They “always have lovers”; men dressed in “tails” [tuxedo] show up at any time of day. The often dyed-blond women are “doll-like” and “melt like butter in the sun” in front of men. Even if the women get themselves into sticky situations, they do not lack for male protectors: their husbands, who are “always heroes” because “heroes always take  their wives back” after the women stray or make trouble. “This is not life,” the magazine reminds its readers, “but only a film,” and while films like Richard Oswald’s 1931 Arm wie eine Kirchenmaus (Poor as a Church Mouse, another light musical comedy, shows women “sitting at the typewriter,” the article comments that the heroine “marries her boss.” An accompanying photograph of a fashionable young woman, lighting a cigarette for her male employer is captioned, “‘Perhaps this will also happen to me,’ thinks the stenographer in the movie theatre and forgets that in real life, this does not happen,” as it wryly concludes. their wives back” after the women stray or make trouble. “This is not life,” the magazine reminds its readers, “but only a film,” and while films like Richard Oswald’s 1931 Arm wie eine Kirchenmaus (Poor as a Church Mouse, another light musical comedy, shows women “sitting at the typewriter,” the article comments that the heroine “marries her boss.” An accompanying photograph of a fashionable young woman, lighting a cigarette for her male employer is captioned, “‘Perhaps this will also happen to me,’ thinks the stenographer in the movie theatre and forgets that in real life, this does not happen,” as it wryly concludes.

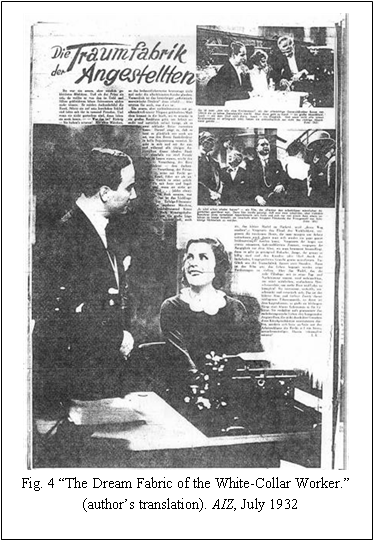

In response to the film industry’s distribution of movies whose protagonists are secretaries, the Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung included an essay entitled “The Dream-Fabric of the White-Collar Worker,” in its July 1932 issue (fig. 4). The article used contemporary cinema as a means to critique bourgeois values and condemned “office film’s” standard romantic plot line in which a secretary marries her employer. A still from The Private Secretary dominates the article’s page. Two others from Poor as a Church Mouse are also included. The images look like those from any other contemporary review found in a middle-class magazine, except the Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung’s article and captions tell their readers how to critically interpret the photos.

The article begins by describing the poor pretty woman, who finds a prince (rich in gold and silver) who rescues her. “What is this!” exclaims the Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung’s reporter. “You’ve guessed! An old fairytale. . .,” one which, transformed for cinema, places the young woman and her prince, not in an enchanted forest or castle, but in the modern, urban workspace. The prince arrives not riding a white horse, but driving an automobile. The young woman does not sweep ashes from the floor, but toils over her typewriter. “Forget about your fears of loneliness,” your “unhappiness at work” because “this happiness of the dream fabric lasts for two hours!” the article notes. It cautions its readers about the insidious power the cinema can wield, saying that “One dreams and hopes . . . this is the highest meaning and lowest aim of the lying romantic films.” Instead, one should see the working class struggle, the real struggle, not the fairytale gender skirmishes projected through the flickering lights of a movie.

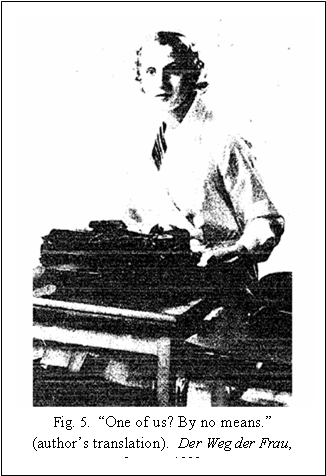

The German illustrated press’s attack on consumer culture’s representations of the woman white-collar worker manifested itself most stridently in the early 1930s when it made Irmgard Keun’s popular novel Gilgi, eine von uns (Gilgi: One of Us) a primary focus. The novel was published first in book form in 1931 and then in serial installments in Vorwärts in August 1932, the year in which it was quickly adapted to film. 11 Der Weg der Frau even included a special section in its January 1933 issue that focused exclusively on the female white-collar worker. Articles in the section discussed the story’s print and film versions and reproduced stills from the movie. Letters from readers in which they described their reactions to the novel and the film, and journalistic coverage of contemporary working conditions in Germany, expanded the stark comparisons between art and real life. The story centers on a twenty-one year old stenotypist, Gisela, or Gilgi, who works as a legal secretary in Cologne. She meets and falls in love with the handsome Martin and quits her job. She becomes pregnant, seeks an abortion, but decides to raise her child by herself. “Gilgi: Film, Novel and Reality,” Der Weg der Frau’s article by Ingeborg Franke, took issue with the film’s melodrama and used a photograph of the film’s fictional heroine. Gilgi sits in front of her typewriter in the office, a telephone and stacks of papers beside her, and looks into the camera with an air of self-confident defiance (fig. 5).

The caption quickly indicates the position of the magazine: “One of us? By no means.”  Franke states that this popular book “does not know at all the female white-collar workers of today” and that this work is a “fantasy of Keun’s – not reality.” To differentiate the distance between fictional and real life, Franke asks, “How does Gilgi live?” In her apartment is a “green, plush sofa,” and despite her many struggles in the narrative, she is still “better off” than her fellow employees. Gilgi also has a savings of 1200 marks. “What stenotypist can do that in reality?” Franke exclaims. Gilgi, she notes, “can do more than the average: in the evening she studies languages (three to begin with and later four – so she can earn more money).” At the centre of the story is a romance that initially has positive outcomes, but turns to tragedy after she decides to leave her lover, and his financial support. However, the story elides the consequences unwed pregnancy usually has for a single woman, and Gilgi decides to raise the child, while going back to work. “That,” writes Franke, meaning the economic and living situation, is “simply impossible.” Moreover, Keun ignores gender politics, even though they are “right under her nose”; there is no “solidarity” at all, remarks the author. While conservative commentators had lamented Keun’s depiction of sexuality, Der Weg der Frau was not disturbed by the story’s portrayal of female desire, but focused its critique on the economic circumstances associated with unwed pregnancy and abortion. Franke states that this popular book “does not know at all the female white-collar workers of today” and that this work is a “fantasy of Keun’s – not reality.” To differentiate the distance between fictional and real life, Franke asks, “How does Gilgi live?” In her apartment is a “green, plush sofa,” and despite her many struggles in the narrative, she is still “better off” than her fellow employees. Gilgi also has a savings of 1200 marks. “What stenotypist can do that in reality?” Franke exclaims. Gilgi, she notes, “can do more than the average: in the evening she studies languages (three to begin with and later four – so she can earn more money).” At the centre of the story is a romance that initially has positive outcomes, but turns to tragedy after she decides to leave her lover, and his financial support. However, the story elides the consequences unwed pregnancy usually has for a single woman, and Gilgi decides to raise the child, while going back to work. “That,” writes Franke, meaning the economic and living situation, is “simply impossible.” Moreover, Keun ignores gender politics, even though they are “right under her nose”; there is no “solidarity” at all, remarks the author. While conservative commentators had lamented Keun’s depiction of sexuality, Der Weg der Frau was not disturbed by the story’s portrayal of female desire, but focused its critique on the economic circumstances associated with unwed pregnancy and abortion.

Three images, two of which are from the film accompany the article, meant to illustrate the illusion of female independence that the story provides. The first shows Gilgi at work, standing in front of her boss’s desk, wearing stylish clothing; the second shows her meeting Martin (the caption notes that “naturally, it is love at first sight”); the third, shows Gilgi in a Mercedes with her lover. The car represents urban, modern mobility and wealth, but Gilgi is the passenger, not the driver. Another photo, larger than the two still-shots from the film is of “the real Gilgi,” an image of a young woman at a typewriter, who is not as pretty or young as the cinematic heroine. Marianne Gundermann, Der Weg der Frau’s editor, added her voice with a brief editorial about the reaction to the Vorwärts’s original serialised novel and to the film, noting that some letters from women protested that the “egotistical Gilgi” was “not one of them.” Others resented that Keun characterised some working women in negative terms – like her description of the “dirty woman who sewed for a living” – or scoffed it would be impossible to buy clothes for 150 marks, as Gilgi does in the book. Gundermann says that she came across a young woman selling flowers on the street who told her “nobody has work for a 19 year old stenotypist. I am one of the million ‘redundant’ people” and “that is the life of a stenotypist in reality.” Juxtaposed with Gundermann’s article is a photograph of women sitting around a small  kitchen table in a cramped apartment, with no plush sofa in sight. The image makes a stark contrast to Gilgi’s depictions, and its inclusion drives home the point that photographs of those “real Gilgis” should prove to the readers that the working-class struggle does not allow for dreams of prince charming or a luxurious apartment. Based on the Vorwärts’s readers’ responses that Der Weg der Frau quoted, working-women were quite critical of the unrealistic representation, even though others found the story and its heroine appealing in a fantasy that offered women agency. kitchen table in a cramped apartment, with no plush sofa in sight. The image makes a stark contrast to Gilgi’s depictions, and its inclusion drives home the point that photographs of those “real Gilgis” should prove to the readers that the working-class struggle does not allow for dreams of prince charming or a luxurious apartment. Based on the Vorwärts’s readers’ responses that Der Weg der Frau quoted, working-women were quite critical of the unrealistic representation, even though others found the story and its heroine appealing in a fantasy that offered women agency.

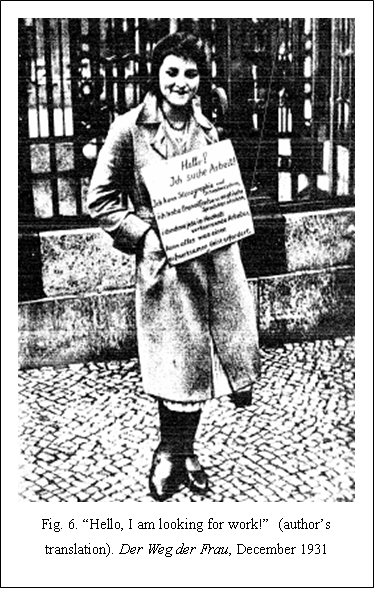

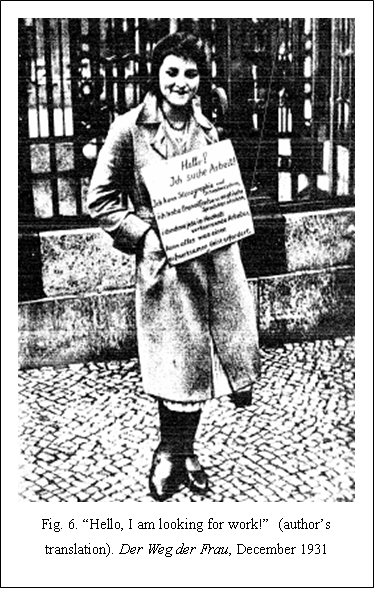

However, even before Gilgi’s sensational impact, Der Weg der Frau had taken a consistent stand on the poor conditions in white-collar work for women. The theme became an important one throughout the entirety of its three-year press run. The image for the cover of the December 1931 issue makes one of the most striking examples (fig. 6). The woman, standing on the sidewalk, with her hands in her pocket, smiles directly at the camera. She is the iconic female white-collar worker. Her short hair, belted coat and lipstick mark her as a typical Neue Frau. But the placard around her neck shows she is more than a figure in a street photograph illuminating urban life. “Hello,” it reads. “I am looking for work! I know stenography and the typewriter. I can speak French and English, I can take any household work, I can do anything that requires an attentive mind.” The caption beneath the photograph states that “She has learned so much . . . and still has no work.” Within the context of the German economic crisis, she represents “one of the millions” who is unemployed. Inside, the regular column “Women in Factories and Offices,” has the bold headline: “Fear of Layoffs.” The article argues that the women employed in offices or department stores experience long working days with low salaries; they work through their short breaks for fear of getting laid off. The magazine notes that what the women need, beyond a better salary, is a forty-hour working week. An accompanying photo depicts a crowd of men and women at a department store which is advertising for fifty female and ten male workers, promising that the women will get paid between thirty-four and fifty marks per month. A few “lucky ones” will get the job. 12 Taken together, these images in Der Weg der Frau function as a “warning” for young women who envision white-collar work as glamorous and ignore the struggles of unemployment.

Although the Nazi illustrated magazine the Illustrierte Beobachter rarely carried images of working-women in its publication, “The Misery of the White-Collar Worker,” published in November 1929, included photographs in its coverage of the high levels of unemployment for female workers. Photographs of numbers of women in line at a Berlin employment office dominate the page. One depicts a group of women standing before the counter of a social worker, an often “humiliating thing,” as the text notes. The article declares that the “concern for daily bread” is “not just the responsibility of men anymore.” However, the article is more than a sympathetic look at female unemployment; it states that “with new rights and obligations, women have assumed a great many discomforts.” While “the latest German statistics” may verify that women are working as much as men, “this victory for women has also brought its drawbacks,” difficulties that reflect not merely the “severity of work” but rather, “the seriousness of unemployment.” Spend a few hours in one of Berlin’s employment offices, the article advocates, to go beyond the statistics’ comforting data. The article continues in its description of a typical day for unemployed women looking for work. At eight in the morning, they wait in line at an employment office for a number. If a woman is lucky, she will find work. But in the worse cases, the women wait months or sometimes an entire year for a job. Occasionally, women may be able to “practice their [typing] skills” but because white-collar jobs are already filled, those opportunities were few.

The Illustrierte Beobachter expresses more than just sympathy for the many unemployed women in Germany, expanding the apprehensions that conditions for the “people who want to work” have left the nation’s population “physically and spiritually desolate.” As an elaborate reminder, the cover image for its March 1, 1930 issue was a photograph of a long row of telephone operators with the bold caption: “Where nerves are exhausted!” For the Illustrierte Beobachter the female white-collar worker’s image symbolised the great and pervasive social discontent as a result of the late Weimar Republic’s high levels of unemployment.

Conclusion

Taken together, these publications speak to the variety of ways in which the figure of the Neue Frau played an important part in defining and defending women’s roles in German society from 1919-1933. The female white-collar worker, although only one symbol of the Neue Frau, was an important visual marker of female modernity for all political parties. Unlike those in mainstream publications for the middle-class female reader, many of the articles and images in the Communist, Social Democratic or Nazi press either criticized or attempted to deconstruct the fantasy image of the white-collar worker in order to suit their particular visions of the future. The communist press juxtaposed representations of the fashionable, urban secretary with visual and written descriptions of “real” workers. It sought to redefine the Neue Frau in relation to the material reality of most working women by emphasizing the gulf between fantastical images of the white-collar worker in contemporary film and the real working conditions for women. The Illustrierte Beobachter employed the white-collar worker as a general symbol of economic instability and worries about women in the workforce. All representations of the female body in relation to white-collar work emphasized class differences between images of the Neue Frau. The contested nature of the images reminds us of the flexibility of the term Neue Frau and its continued resonance in the post-World War I era.

Jennifer Lynn is an assistant Professor of History and the Director of the Women’s and Gender Studies Center at Montana State University Billings. Her work has appeared in Connections and she is currently working on a manuscript, Contested Femininities: Representation of the Modern Woman in the German Illustrated Press, 1920 – 1960.

Notes

1 For a discussion of the German new woman see Ankum, Huyssen, and Petro. For the Neue Frau’s role in cultural production see Meskimmon and West, Berghausu, Petersen, and McCormick.

2 In my larger project, I argue that these observations hold true, not only for the Weimar Republic (the “laboratory of modernity”) and the “reactionary modernity” of the Third Reich, but also for the increased competition between East and West Germany, where the Moderne Frau was touted as a symbol for the most progressive, equal and “emancipatory” society. Eisenstadt and Sachsenmaier provide important discussions of “multiple modernities.”

3 For a discussion of women, sexuality and ideas of modernity see Rowe, Kosta, and Weinbaum.

4 Knoch and Stöber provide an in-depth overview of the development of the illustrated press.

5 For a discussion of women in auxiliary groups see Schönberger and both texts by Davis.

6 Both Balderston and Bessel provide important discussions related to demobilisation.

7 Hagemann’s 1990 Frauenalltag und Männerpolitik: Alltagsleben und gesellschaftliches Handeln von Arbeiterfrauen in der Weimarer Republik demonstrates women’s extensive contributions to grassroots political activism

8 Grossman provides a thorough discussion about this approach and its influence.

9 For a discussion of the commercialised image of the Neue Frau in literature which exemplifies these narratives see Peterson, Harrigan, King, and Nottelmann.

10 Very little content changed in the more mainstream Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung, but publications affiliated with all engaged with debates surrounding women’s paid work, especially in the late 1920s and early 1930s with the Great Depression and the Weimar Republic’s political upheaval. 1930 also saw the publication of, Siegfried Kracauer’s influential Die Angestellen (The Salaried Masses), which focused on the new white-collar workers of the Weimar Republic and their desire for distraction through entertainment.

11 Keun’s novel has been the focus of much scholarship related to issues of Weimar modernity. For example, see Kosta, “Unruly Daughters,” Ankum and Rainey.

12 See also the article in WDF’s May 1932 issue, Hard Work = Typing.” The article, which does not include an image, notes sarcastically, “What a desire – to be a stenotypist!” While the “office films” show the job “ending in marriage between the blond-haired girl and her employer,” in reality the work is “stressful” and hard on the nerves, with long days and little pay.

Works Cited

Primary Sources

Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung. Berlin: Neuer Deutscher Verlag, 1924-1933. Print.

Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung. Berlin: Ullstein & Co., 1918-1945. Print.

Der Weg der Frau. Berlin: Carlo Sabo, 1931 – 1933. Print.

Frauenwelt: eine Halbmonatsschrift. Berlin: Dietz, 1924 – 1933. Print.

Illustrierte Beobachter. München: Franz Eher Verlag, 1926-1945. Print.

Secondary Sources

Ankum, Katherina von, ed. Women in the Metropolis: Gender and Modernity in Weimar Culture. Berkeley: U of California P, 1997. Print.

Balderston, Theo. Economics and Politics in the Weimar Republic. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2002. Print.

Berghaus, Gunter. “Girkultur: Feminism, Americanism, and Popular Entertainment in Weimar Germany.” Journal of Design History 1 (1998): 193-219. Print.

Bessel, Richard. Germany after the First World War. Oxford: Clarendon, 1993. Print.

Bridenthal, Renate, and Claudia Koonz. “Beyond Kinder, Küche, Kirche: Weimar Women in Politics and Work.” When Biology Became Destiny: Women in Weimar and Nazi Germany. Ed. Renate Bridenthal, Atina Grossman, and Marion A. Kaplan. New York: Monthly Rev. P, 1984. 33-65. Print.

Daniel, Ute. Arbeiterfrauen in der Kriegsgesellschaft: Beruf, Familie und Politik im Ersten Weltkrieg. Gӧttingen: Vandenhoek & Ruprech. 1989. Print.

Davis, Belinda. Home Fires Burning: Food, Politics and Everyday Life in World War I. Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina P, 2000. Print.

--. “The Personal is the Political: Gender, Politics, and Political Activism in Modern German History.” Gendering Modern German History: Rewriting Historiography. Ed. Karen Hagemann and Jean H. Quataert. New York: Berghahn, 2007. 107-27. Print.

Eisenstadt, Shmuel N. “Multiple Modernities.” Multiple Modernities. Ed. Eisenstadt. New Brunswick: Transaction, 2002. 1-29. Print.

Frevert, Ute.“Traditional Weiblichkeit und moderne Interessenorganisation: Frauen im

Angestelltenberuf 1918-1933. Geschichte und Gesellschaft 7 (1981): 504-33. Print.

---. Women in German History: From Bourgeois Emancipation to Sexual Liberation. Oxford: Bloomsbury, 1990. Print.

Grossmann, Atina. “Continuities and Ruptures: Sexuality in Twentieth-Century Germany:

Historiography and Its Discontents.” Gendering Modern German History. Ed. Karen Hagemann and Jean H. Quataert. New York: Berghahn, 2007. 208-27. Print.

Hagemann, Karen. “Ausbildung für die ‘weibliche Doppelrolle.’” Geschlechterhierarchie und Arbeitsteilung: Zur Geschichte ungleicher Erwerbschancen von Männern und Frauen. Ed. Karin Hausen. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1993. 214-35. Print.

--. “Der ‘Traumberuf’ der Kontoristin: Wunschbilder und Wirklichkeiten weiblicher Büroarbeit

in der Weimarer Republic.” Europe im Zeitalter des Industrialismus. Zur“Geschichte von unten” im europäischen Vergleich. Ed. Elisabeth v. Dücker, Karin Haist, and Ursula Schneider. Hamburg: Dölling und Galitz, 1993. 187-98. Print.

---. Frauenalltag und Männerpolitik: Alltagsleben und gesellschaftliches Handeln von

Arbeiterfrauen in der Weimarer Republik. Bonn: JHW Dietz Nachf, 1990. Print.

Hardt, Hanno. “Photography for the Masses: Photography and the Rise of Popular Magazines in Weimar Germany.” Journal of Communication Inquiry 13 (1989): 7-30. Print.

Harrigan, Renny. “Die emanzipierte Frau im deutschen Roman der Weimarer Rebuplik.”

Sterotyp und Voruteil in der Literatur. Ed. James Elliot, et al. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, 1978. 65-83. Print.

Huyssen, Andreas. “Mass Culture as Woman: Modernism’s Other.” Studies in Entertainment:

Critical Approaches to Mass Culture.” Ed. Tania Modleski. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1986. 188-207. Print.

Jones, Amelia. “Conceiving the Intersection of Feminism and Visual Culture.” The Feminism

and Visual Culture Reader. Ed. Jones. London: Routledge, 2003. 1-8. Print.

King, Lynda J. Bestsellers by Design: Vicki Baum and the House of Ullstein. Detroit: Wayne

State UP, 1988. Print.

Knoch, Habbo. “Living in Pictures: Photojournalism in Germany, 1900 to the 1930s.” Mass

Media, Culture and Society in Twentieth Century Germany. Ed. Karl Christian Führer and Corey Ross. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006. 217-33. Print.

Kosta, Barbara. “Cigarettes, Advertising and the Weimar Republic’s Moderne Frau.” Visual

Culture in Twentieth-Century Germany: Text as Spectacle. Ed. Gail Finley. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 2006. 134-53. Print.

---. “Unruly Daughters and Modernity: Irmgard Keun’s Gilgi: eine von uns.” German Quarterly

68 (1995): 271-86. Print.

Kundrus, Birthe. “Gender Wars.” Home/Front: The Military, War and Gender in Twentieth Century Germany. Ed. Karen Hagemann and Stefanie Schüler-Springorum. Oxford: Berg, 2002. 159-80. Print.

McCormick, Richard W. Gender and Sexuality in Weimar Modernity: Film, Literature and

“New Objectivity.” New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001. Print.

Meskimmon, Marsha, and Shearer West, eds. Visions of the ‘Neue Frau’: Women and the Visual

Arts in Weimar Germany. Aldershot: Scolar P, 1995. Print

Nottelmann, Nicole. Die Karrieren der Vicki Baum. Cologne: Kiepenheuer & Witsch, 2007.

Print.

Petersen, Vibeke Rützou. Women and Modernity in Weimar Germany: Reality and

Representation in Popular Fiction. New York: Berghahn, 2001. Print.

Petro, Patrice. Joyless Streets: Women and Melodramatic Representation in Weimar Germany.

Princeton: Princeton UP, 1989. Print.

---. “Modernity and Mass Culture in Weimar Germany: Contours of a Discourse on Sexuality in Early Theories of Perception and Representation.” New German Critique 40 (1987): 115-46. Print.

Rainey, Lawrence. “Fables of Modernity: The Typist in Germany and France.” Modernism/Modernity 11 (2004): 333-40. Print.

Rouette, Susanne. “Nach dem Krieg: Zurück zur ‘normalen’ Hierarchie der Geschlechter."

Geschlechterhierarchie und Arbeitsteilung: Zur Geschichte ungleicher Erwerbschancen von Männern und Frauen. Ed. Karin Hausen. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1993. 167-90. Print.

Rowe, Dorothy. Representing Berlin: Sexuality and the City in Imperial and Weimar Germany. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2003. Print

Sachsenmaier, Dominic, et al. Reflections on Multiple Modernities: European, Chinese and

Other Interpretations. Leiden: Brill, 2002. Print.

Schönberger, Bianca. “Motherly Heroines and Adventurous Girls: Red Cross Nurses and

Women Army Auxiliaries in the First World War.” Ed. Karen Hagemann and Stefanie Schüler-Springorum. Home/Front: The Military, War and Gender in Twentieth Century Germany. Oxford: Berg, 2002. 87-114. Print.

Scott, Joan. “Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis.” American Historical Review 98 (1986): 1053-75. Print.

--. “Unanswered Questions.” AHR Forum: Revisiting “Gender as a Category of Historical

Analysis.” The American Historical Review. 113.5 (2008): 1344-45. Print.

Sneeringer, Julia. Winning Women’s Votes: Propaganda and Politics in Weimar Germany. Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina P, 2002. Print.

Stöber, Rudolf. Deutsche Pressegeschichte. Konstanz: UVK-Medien, 2000. Print.

Wagner, Peter, ed. Icons, Iconotexts: Essays on Ekphrasis and Intermediality. Berlin: W. de Gruyter, 1996. Print.

Weinbaum, Alys Eve, et al. The Modern Girl Around the World: Consumption, Modernity and

Globalization. Durham: Duke UP, 2008. Print. |

Criticising women who “dream of being slim” the Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung included photographs of the latest beauty techniques. A woman has her face and neck massaged, because “one can, through this paraffin mask, stay ‘young and beautiful.’” Another photograph shows a woman lounging on a bed, “wrapped in a paraffin binding” in order to gain an “elegant and slim” body. In another, a serious looking man, in a white lab coat, dyes a “rich woman’s hair”; however, it is a “headache inducing treatment” (fig. 3) and the article calculates daily beauty routines in terms of time wasted and money spent.

Criticising women who “dream of being slim” the Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung included photographs of the latest beauty techniques. A woman has her face and neck massaged, because “one can, through this paraffin mask, stay ‘young and beautiful.’” Another photograph shows a woman lounging on a bed, “wrapped in a paraffin binding” in order to gain an “elegant and slim” body. In another, a serious looking man, in a white lab coat, dyes a “rich woman’s hair”; however, it is a “headache inducing treatment” (fig. 3) and the article calculates daily beauty routines in terms of time wasted and money spent.  their wives back” after the women stray or make trouble. “This is not life,” the magazine reminds its readers, “but only a film,” and while films like Richard Oswald’s 1931 Arm wie eine Kirchenmaus (Poor as a Church Mouse, another light musical comedy, shows women “sitting at the typewriter,” the article comments that the heroine “marries her boss.” An accompanying photograph of a fashionable young woman, lighting a cigarette for her male employer is captioned, “‘Perhaps this will also happen to me,’ thinks the stenographer in the movie theatre and forgets that in real life, this does not happen,” as it wryly concludes.

their wives back” after the women stray or make trouble. “This is not life,” the magazine reminds its readers, “but only a film,” and while films like Richard Oswald’s 1931 Arm wie eine Kirchenmaus (Poor as a Church Mouse, another light musical comedy, shows women “sitting at the typewriter,” the article comments that the heroine “marries her boss.” An accompanying photograph of a fashionable young woman, lighting a cigarette for her male employer is captioned, “‘Perhaps this will also happen to me,’ thinks the stenographer in the movie theatre and forgets that in real life, this does not happen,” as it wryly concludes.  Franke states that this popular book “does not know at all the female white-collar workers of today” and that this work is a “fantasy of Keun’s – not reality.” To differentiate the distance between fictional and real life, Franke asks, “How does Gilgi live?” In her apartment is a “green, plush sofa,” and despite her many struggles in the narrative, she is still “better off” than her fellow employees. Gilgi also has a savings of 1200 marks. “What stenotypist can do that in reality?” Franke exclaims. Gilgi, she notes, “can do more than the average: in the evening she studies languages (three to begin with and later four – so she can earn more money).” At the centre of the story is a romance that initially has positive outcomes, but turns to tragedy after she decides to leave her lover, and his financial support. However, the story elides the consequences unwed pregnancy usually has for a single woman, and Gilgi decides to raise the child, while going back to work. “That,” writes Franke, meaning the economic and living situation, is “simply impossible.” Moreover, Keun ignores gender politics, even though they are “right under her nose”; there is no “solidarity” at all, remarks the author. While conservative commentators had lamented Keun’s depiction of sexuality, Der Weg der Frau was not disturbed by the story’s portrayal of female desire, but focused its critique on the economic circumstances associated with unwed pregnancy and abortion.

Franke states that this popular book “does not know at all the female white-collar workers of today” and that this work is a “fantasy of Keun’s – not reality.” To differentiate the distance between fictional and real life, Franke asks, “How does Gilgi live?” In her apartment is a “green, plush sofa,” and despite her many struggles in the narrative, she is still “better off” than her fellow employees. Gilgi also has a savings of 1200 marks. “What stenotypist can do that in reality?” Franke exclaims. Gilgi, she notes, “can do more than the average: in the evening she studies languages (three to begin with and later four – so she can earn more money).” At the centre of the story is a romance that initially has positive outcomes, but turns to tragedy after she decides to leave her lover, and his financial support. However, the story elides the consequences unwed pregnancy usually has for a single woman, and Gilgi decides to raise the child, while going back to work. “That,” writes Franke, meaning the economic and living situation, is “simply impossible.” Moreover, Keun ignores gender politics, even though they are “right under her nose”; there is no “solidarity” at all, remarks the author. While conservative commentators had lamented Keun’s depiction of sexuality, Der Weg der Frau was not disturbed by the story’s portrayal of female desire, but focused its critique on the economic circumstances associated with unwed pregnancy and abortion. kitchen table in a cramped apartment, with no plush sofa in sight. The image makes a stark contrast to Gilgi’s depictions, and its inclusion drives home the point that photographs of those “real Gilgis” should prove to the readers that the working-class struggle does not allow for dreams of prince charming or a luxurious apartment. Based on the Vorwärts’s readers’ responses that Der Weg der Frau quoted, working-women were quite critical of the unrealistic representation, even though others found the story and its heroine appealing in a fantasy that offered women agency.

kitchen table in a cramped apartment, with no plush sofa in sight. The image makes a stark contrast to Gilgi’s depictions, and its inclusion drives home the point that photographs of those “real Gilgis” should prove to the readers that the working-class struggle does not allow for dreams of prince charming or a luxurious apartment. Based on the Vorwärts’s readers’ responses that Der Weg der Frau quoted, working-women were quite critical of the unrealistic representation, even though others found the story and its heroine appealing in a fantasy that offered women agency.